Liver disease

Take home messages

- Liver disease carries substantial peri-operative morbidity and mortality

- Not all liver patients are coagulopathic

- A damaged liver messes with your pharmacology, and all of your other organs

Livers are scary

Even experienced anaesthetists are usually suitably spooked by severe liver disease, and rightly so, as the various functions of the liver are intricately intertwined with pretty much every other organ system in the body.

If the liver gets sick, so does a whole lot of the rest of the body.

We'd be mad to try and cover the entirety of 'liver stuff' in one post, so here we're going to focus on the implications of chronic liver disease when you're trying to anaesthetise the patient for something else, like an appendix at three in the morning.

So let's start with a favourite question - what does the liver actually do?

What does the liver do?

In today's episode of categorise or die, we're splitting the liver's numerous functions into synthesis, storage and metabolism and clearance.

Synthesis

- Albumin

- CRP

- Clotting factors

- Bile acids

- Antithrombin III

- Immunoglobulins

- Lymph

Storage

- Iron

- Vitamins

- Glycogen

Metabolism and clearance

- Carbohydrate

- Protein

- Fat

- Bilirubin

- Hormones

- Drugs

If you're answering this question as part of a CRQ, give at least one answer from each section, as sometimes they limit the number of marks awarded to each of them.

What anatomy do I need to know?

The liver is a peculiar organ with many secrets, a strange blood supply and a delightful hexagonal structure that is prime OSCE and SOE fodder.

Here are our highest yield facts about liver anatomy:

- The liver is generally around 1.8kg and has a dual blood supply - hepatic artery and portal vein

- It receives 25% of the cardiac output (70% from portal vein, 30% from hepatic artery)

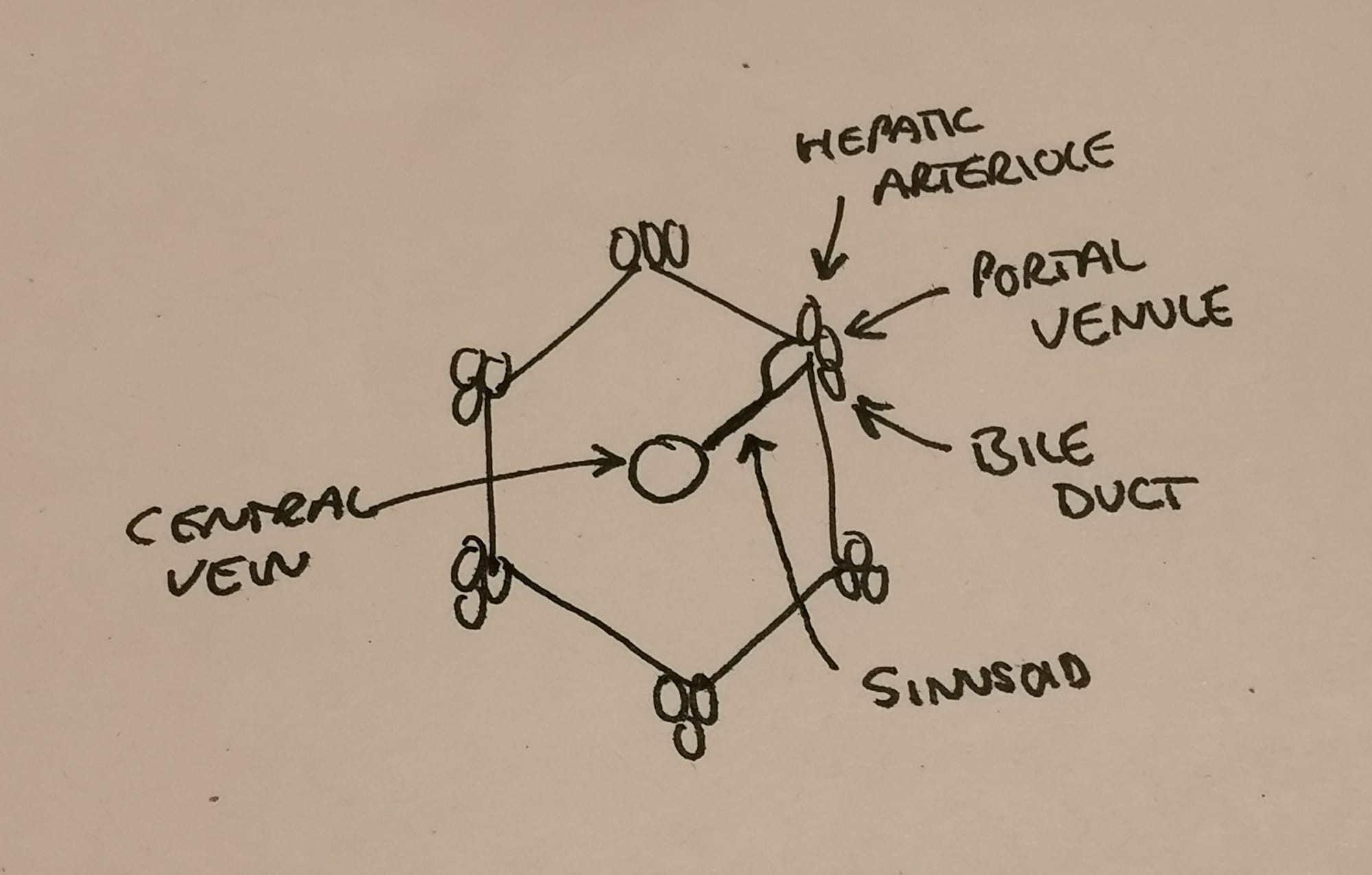

- The functional unit is the hexagonally shaped lobule that has a portal triad at each corner (bile duct, portal venule and hepatic arteriole)

- The hepatic arteriole and portal venule join forces to form the sinusoid, which drains into the central vein, then the hepatic vein, and finally the IVC

- Bile is produced by hepatocytes and then altered and concentrated by cholangiocytes, before draining into the bile canaliculi and into the bile ducts

- Kupffer cells are monocytes that live in the sinusoids and recover iron from senescent red blood cells

What is liver disease?

As you might imagine, 'liver disease' is rather a broad term and encompasses a wide variety of pathologies, but there are a couple of terms you need to be able to define.

Acute liver failure

- Also referred to as fulminant liver failure

- Jaundice, coagulopathy and encephalopathy

- This has to be new onset - i.e. the liver was alright before

We use the O'Grady classification, which measures time from jaundice to encephalopathy:

- Hyperacute = <7 days

- Acute = <4 weeks

- Sub-acute = <12 weeks

Chronic liver disease

- This is a much slower, grumbling process of deteroration that occurs over at least 28 weeks or 6 months depending on which source you're using

- Here there is a progressive destruction of the liver's architecture, with chronic inflammation resulting in previously healthy tissue being replaced by nodules of fibrosis

- This in turn leads to a steady decline in liver function

- Chronic liver disease is either compensated, with no symptoms and normal(ish) LFTs, or decompensated, with jaundice, variceal bleeding, ascites or encephalopathy

Frequently the journey of chronic liver disease is studded with episodes of acute functional deterioration, which we refer to as acute-on-chronic liver disease.

Acute on chronic liver failure carries high mortality with often multiple organ dysfunction.

What are the common causes of chronic liver disease?

- Viral hepatitis

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Alcoholic liver disease

- Cryptogenic liver disease

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Sclerosing cholangitis

- Venous outflow obstruction

- Drugs

- Metabolic disease (Wilson's, haemochromatosis, alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency)

It's not just the liver

As you might expect, and as we alluded to earlier, a sick liver isn't just a sick liver - it's a sick everything else as well.

A remarkably popular and understandably important question is precisely that - 'what other problems does it cause?'

What are the extrahepatic manifestations of liver disease?

This is an enormous answer, so break it down by system, and give one or two examples from each.

Cardiovascular

- Increased cardiac output and lower systemic vascular resistance (hyperdynamic circulation)

- Splanchnic vasodilatation and functional hypovolaemia

- Diastolic dysfunction, QT prolongation and poor response to stress (cirrhotic cardiomyopathy)

Respiratory

- Ascites can cause diaphragmatic splinting and reduction in FRC

- Pleural effusions (hepatic hydrothorax)

- Hepatopulmonary syndrome (due to arteriovenous shunting within the lung)

- Portopulmonary hypertension (pulmonary vasoconstriction and vascular remodelling)

Gastro

- Varices

- Splenomegaly

- Ascites

- Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis

Renal

- Hepatorenal syndrome

Haematological

- Anaemia

- Coagulopathy

- Hypofibrinoginaemia

- Thrombocytopenia

Neuro

- Hepatic encephalopathy (reversible encephalopathy due to accumulation of ammonia, short-chain fatty acids and mercaptans)

- Asterixis

Endocrine

- Hypoglycaemia

- Hypoalbuminaemia

- Adrenal insufficiency

- Secondary hyperaldosteronism leading to water retention and hyponatraemia

Other

- Malnutrition

- Muscle wasting

- Poor wound healing

Anticoagulation

We know the liver makes clotting factors, and that liver patients often present with a bad case of the bleedies, but the evidence suggests now that actually liver patients aren't hugely more likely to bleed.

This is because they're equally deficient in the anti clotting factors as they are the pro clotting ones, and hence they reach a new - albeit dysfunctional - haemostatic balance.

What are the clotting factor changes seen in liver disease?

Deranged procoagulant factors

- Hypofibrinogenaemia

- Vitamin K deficiency

- Thrombocytopenia

- Reduced thrombopoeitin

- Reduced factors 2, 5, 7, 9, 10 and 11

- Increased t-PA

Deranged anticoagulant factors

- Increased vWF

- Reduced protein C

- Reduced protein S

- Reduced antithrombin

- Reduced plasminogen

This means that measuring INR by itself probably isn't giving a complete picture of the patient's haemostatic status, and it shouldn't be used as the sole guidance of the patient's management.

Clearly an INR of 12 is still bad, but don't be overly reassured or terrified by an INR of 1.8, especially if the patient is septic.

What happens to the platelets?

Generally liver patients have fewer platelets knocking around, mainly due to sequestration by the spleen, but the ones that are there generally do work, boosted by the increased vWF concentrations.

A lot of the bleeding issue is due to increased venous pressure, which is going to make things work in even the most clotty of patients.

How does it affect my anaesthetic?

The astute candidate will have realised that the answer to this question is always to break the response down into the same three temporal categories, to encompass your pre-operative, intra-operative and post-operative concerns.

Preoperative

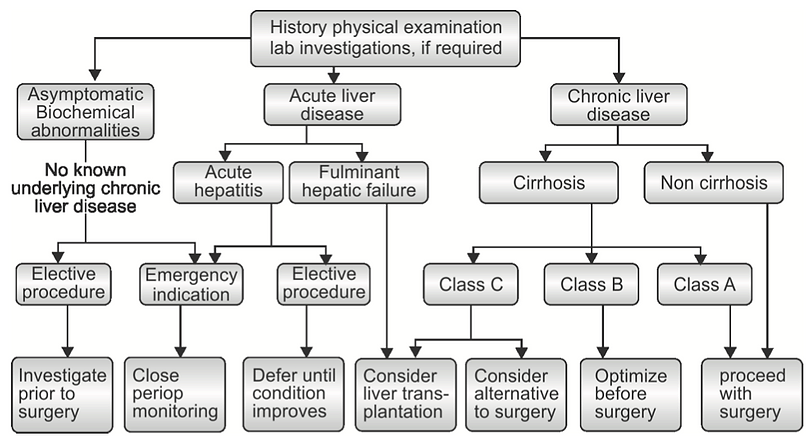

"I should like to take a thorough history and perform a physical examination, followed by relevant imaging and investigations to inform my anaesthetic assessment."

Clearly the aim here is to identify how bad the liver disease is, and to highlight any areas that can be improved or optimised prior to surgery. Sometimes it's so bad that surgery needs to be postponed or abandoned altogether.

As you might imagine, the urgency and severity of the operation will affect what you can achieve in the preoperative period.

The main things you're trying to optimise or prevent in the perioperative period are:

- Ascites

- Renal function

- Encephalopathy

- Acid-base balance

- Electrolytes

- Coagulopathy

If the patient needs life-saving emergency surgery then your hand is somewhat forced, but you should still try and pre-optimise as much as possible beforehand, and definitely escalate to the most senior person who will listen.

What are the key features of the anaesthetic history and examination in patients with liver disease?

- Severity of disease

- Extrahepatic manifestations

- Evidence of decompensation

- Sepsis

- Steroids

- Ascites

- Pleural effusion

What preoperative investigations can be of use in patients with liver disease?

- Full blood count

- Urea, creatinine and electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Clotting

- ECG

- Echocardiography

- CPET

- ABG

- Chest Xray

- Ultrasound abdomen to assess portal venous pressures

What do I do about their clotting?

Patients with chronic liver disease tend to reach a strange semi-stable 'balance' in which they're not substantially more likely to clot or to bleed than other patients.

The reason they have such spectacular GI bleeds generally comes as a result of raised portal venous pressure and splanchnic congestion, rather than an inability to clot properly.

As a result, we shouldn't reflexively manage raised INRs with FFP or cryoprecipitate. Not only do these not do much below an INR of around 1.7, it doesn't seem to help anyway.

TEG or ROTEM are generally much better options to allow you to correct abnormalities on the fly.

That being said, there are several things that you can do if you're worried about coagulopathy:

- Vitamin K - will help with nutritional/bile salt deficiency, but won't do much if they've got substantial hepatic synthetic failure

- FFP - if actively bleeding with a prolonged PT

- Platelets - if less than 50 000 and actively bleeding or major surgery

- Cryoprecipitate - if you're struggling

Intraoperative

Intraoperative concerns generally fall into the following sections:

- What monitoring do I need?

- What should I do with my drugs?

- What am I worried is going to go wrong?

What monitoring should I use?

- All your standard AAGBI monitoring - ECG, BP, Saturations, ETCO2 etc

- Urine output - catheter

- Invasive blood pressure monitoring is advised in significant liver disease

- Consider a central line in patients with a high MELD score, to facilitate electrolyte correction, but remember CVCs carry risk in this patient cohort

Big fluid shifts can take you by surprise, especially if large volumes of ascites are going to be drained, so preemptive monitoring and fluid therapy is warranted.

If you're draining lots of ascites remember the need for human albumin replacement.

What are the pharmacological considerations for anaesthesia in liver disease?

- Propofol has more pronounced cardiac and respiratory depressant effects in liver disease

- Atracurium may be of benefit due to its metabolism not relying on hepatic function, although protein binding and volume of distribution changes may require a larger dose

- Rocuronium can have a prolonged elimination

- Reduced pseudocholinesterase concentrations can prolong duration of blockade with suxamethonium

- Volatile anaesthesia and TIVA are both acceptable options, however TIVA may be better as remifentanil is metabolised by red blood cell esterases, which are preserved in liver disease

- Morphine has prolonged effects due to reduced extraction ratio and hepatic blood flow, so fentanyl is preferred for postoperative pain control

- NSAIDs are generally avoided for risk of renal toxicity, platelet dysfunction and GI bleeding

- Paracetamol should be used in liver disease to reduce opioid requirements, but caution in severe hepatic dysfunction

In general it seems that anaesthetic technique doesn't matter too much, as long as you're thinking about and dealing with all the liver-related problems.

Easier said than done.

What is likely to go wrong?

- Haemodynamic instability

- Bleeding and coagulopathy

- Drug metabolism and encephalopathy

- Oliguria and acute kidney injury

- Hypoglycemia

- Electrolyte disturbance*

*Pay particular attention to calcium if you're giving blood products.

What should I do with my fluids?

Yeah good question.

- Severe liver disease patients seem to be both dry and overloaded at the same time

- They retain sodium like mad, and renal function can often deteriorate despite plenty of filling

- Try and avoid hypervolaemia, and keep a close eye on potassium

- Goal directed fluid therapy targetting urine output or cardiac output monitoring parameters is probably a good idea

- One can always 'consider albumin' especially in the presence of ascites

- Vasopressors shouldn't be forgotten either, as these patients often have low systemic vascular resistance

- If you're giving blood, give it as slowly as you can get away with - to allow the tired liver to process the citrate

- Don't forget glucose

Other considerations

- Positive pressure ventilation and PEEP can worsen hepatic venous pressure, with knock on effects on cardiac output

- Avoid hyperventilation as hepatic blood flow is reduced by hypocarbia

- Avoid excessive airway and oesophageal instrumentation as there is risk of bleeding - nasal intubation is usually avoided

- Even fasted patients can regurgitate if they have ascites or hiatus hernia

- Viral hepatitis can pose a threat to staff via needle stick injury

Post-operative

The main issues here are:

- Where is my patient going afterwards? (The answer is usually ITU)

- Am I extubating or keeping them asleep?

- What problems are they likely to encounter in the postoperative period?

What are the post operative considerations for patients with liver disease?

Patients with liver disease have a much less effective stress response to trauma and surgery, meaning they're more likely to get any of multiple complications:

- Wound dehiscence and infection

- Bacterial peritonitis

- Respiratory tract infection

- Acute kidney injury

- Decompensated liver failure

The most pressing issue is whether the surgery and anaesthesia is going to trigger a decompensation of their liver failure, so generally patients should be monitored closely on HDU or ITU after anything other than the most minor of procedures.

The decision to remain intubated rather than extubating at the end of surgery should be guided by the following indications:

- Severity liver disease

- Duration and extent of surgery

- Known associated cardiac or pulmonary disease

- Significant fluid or electrolyte disturbance

- Hypothermia

- Preoperative encephalopathy

- Oxygen saturations <90% on 40% oxygen

Any signs of liver decompensation should be discussed immediately with a specialist liver centre.

- VTE needs individual assessment and management based on surgical and haematology team input

- Laxatives to avoid encephalopathy

- Careful monitoring of fluid balance and renal function, as high risk of hepatorenal syndrome

- Avoidance of both hypo and hyperglycaemia as both carry increased mortality and morbidity

- Enteral nutrition seems to be better for hepatic function than parenteral

How risky is it?

It would be nice, before embarking on a potentially catestrophic anaesthetic for a patient with liver disease, to know what kind of risk we're talking about.

Handily, there are multiple calculators we can use to guide our risk stratification.

Child-Turcotte-Pugh score

Also called the Child-Pugh score, this uses the following parameters:

- Bilirubin

- Albumin

- INR

- Encephalopathy (how bad)

- Ascites (present or not)

It then churns out three levels - A, B and C - to give an idea of postoperative mortality and morbidity.

- 5-6 = Class A = <5% operative mortality

- 7-9 = Class B = 25%

- 10-15= Class C = >50%

It's used for both hepatic and non-hepatic surgery, and its main drawback is the degree of subjectiveness when assessing the severity of encephalopathy and ascites.

It also has rather arbitrary cut off values.

MELD score

- The MELD score uses creatinin, bilirubin and INR to generate a score

- MELD score <10 is similar to CP A = consider proceding with caution

- MELD 10-15 or CP B = optimise patient then consider proceding with caution

- MELD >15 or CP C = avoid surgery wherever possible

There are multiple variations of the MELD score such as the MELDNa and UKELD scores, but they all do very similar things.

Mayo Clinic cirrhosis calculator

This uses the following data points to predict postoperative mortality in patients with cirrhosis:

- Age

- ASA

- Cause of cirrhosis

Doesn't get examined much, and misses a few key things like severity of portal hypertension which are quite important.

VOCAL-Penn model

This relatively new calculator incorporates the following:

- Platelets

- Albumin

- Bilirubin

- Age

- ASA

- Obesity

- Presence of fatty liver disease

- Emergency surgery and category

This one seems to be pretty good but is still under investigation, and as always risk calculators should form part of the assessment, not guide it entirely.

Yes or No?

Sometimes the answer to this question is easy, often because the decision is largely made for you:

- Stable chronic liver disease presenting with acute bowel perforation needing life-saving laparotomy - yes

- Acute-on-chronic liver failure with ascites, jaundice and encephalopathy for elective ankle fusion - absolutely not

But a lot of the time it's not so clear cut, so the answer (as always) is to involve a 'multidisciplinary team' to guide the decision making process, and usually you'll escalate the decision to your consultant fairly promptly.

While it certainly won't be the remit of the anaesthetic trainee to decide whether or not elective surgery should go ahead for a patient with known liver disease, it's important to appreciate how those decisions are made.

You know - for when it is your decision in like... five years time?

What are the contraindications to elective surgery?

- Acute hepatitis - viral or alcoholic

- Fulminant hepatic failure

- Severe chronic hepatitis

- Child Pugh C cirrhosis

- Severe uncontrolled coagulopathy

- Severe extrahepatic complications (cardiomyopathy, heart failure, renal failure)

Useful Tweets and Resources

Here's a fabulous run through from our good friends over at ABCs of Anaesthesia.

Extrahepatic manifestation of chronic liver disease; Implications for the anaesthetist@BJAJournals #BJAEducation#Anaesthesia, #PeriOpMedhttps://t.co/qp7KVg2Koo pic.twitter.com/gZdFYMOhBn

— British Journal of Anaesthesia (@BJAJournals) March 11, 2022

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.