What is a ‘normal anaesthetic?’

If you’re wondering what an anaesthetist actually does to drift a patient off to sleep for an operation, then please join us for a gentle wander through a standard, low-stress elective operation.

Remember that anaesthetics is a craft, much like carpentry or cooking, with many different ways of achieving a good result and a happy patient, so the following is just one example of how to anaesthetise someone, rather than an all-encompassing definitive guide.

After the team briefing with the surgeons and theatre staff, in which the patient and their case are discussed and the surgical and anaesthetic plans agreed upon, the patient is ‘sent for’, meaning the ward is informed that the patient can now be brought up to theatres for their operation. The surgeons disappear and the anaesthetic team get their equipment and drugs ready.

Drugs

There are generally two categories of drugs to draw up and get ready for an elective procedure; those for induction of anaesthesia, and emergency drugs, which are kept on hand to deal with any urgent problems during the procedure.

The basic recipe for a general anaesthetic is as follows

An induction agent

Also known as a sedative, this induces a profoundly deep sleep, rendering the patient unaware of their surroundings and the procedure. Typically we will use propofol, or ketamine if we’re concerned about the patient’s blood pressure being too low. I like to give a little bit of lidocaine local anaesthetic into the cannula as well, to numb the vein before the propofol is injected, because propofol can sting as it is very irritant to the inside of the vein.

A strong, fast-acting opioid painkiller

This reduces the body’s stress response to the physical process of intubation, and also provides pain relief for the beginning of the operation. Frequently fentanyl or alfentanil are used as a bolus injection, or remifentanil as an infusion, because it is so short acting that a bolus would wear off too quickly.

A muscle relaxant

Neuromuscular blocking agents, or muscle relaxants, are used to paralyse the vocal cords, and allow the endotracheal (breathing) tube to be inserted into the trachea without the patient coughing and going into laryngospasm. The agent of choice was previously either atracurium or suxamethonium, but now more commonly rocuronium is used.

Antiemetics

These are given to offset the sickness caused by some of the drugs and the effects of the surgery itself. Ondansetron and dexamethasone are classic examples, but others such as cyclizine and droperidol can also be used, depending on the anaesthetist’s preference.

Long acting pain relief

Usually morphine, given at the beginning of the operation as it takes 20-40 mins to have peak effect. Other pain relief options include paracetamol, NSAIDS such as diclofenac, and clonidine and magnesium also can be used.

Antibiotics

Not all operations require antibiotics, but anything involving the intestines or orthopaedic implants such as a hip or knee replacement will need at least one dose of antibiotic, which is usually given just after induction of anaesthesia.

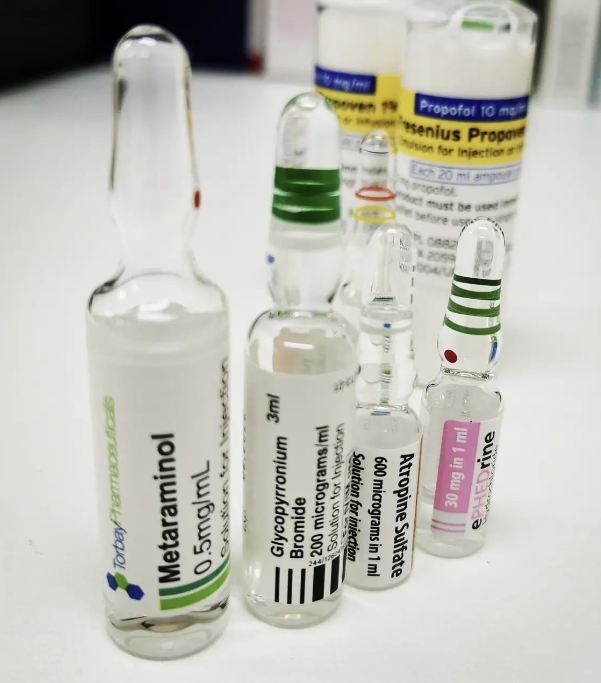

Emergency Drugs

The emergency drugs are essentially rescue therapies for if the unexpected happens during an operation, for example if the patient’s blood pressure or heart rate drop dangerously low as a result of the anaesthetic or the surgery itself.

As with all things anaesthetics, the choice of drugs depends again on personal choice but I usually have ephedrine, metaraminol, atropine and glycopyrrolate at the ready. As well as being useful to have immediately available, they’re also source of psychological comfort to have at your side when venturing into the murky waters of unconsciousness!

The arrival of the patient

As the patient arrives, the anaesthetic team introduce themselves and run through a sign-in checklist to confirm that the correct patient has turned up expecting the right procedure. If they’re having limb surgery, it is confirmed with the patient which side they’re expecting the operation, left or right, and that there is a visible mark on the correct limb, drawn by the surgeon. They’re then brought into theatre. Before anything else happens, three bits of monitoring are applied:

- Pulse oximeter

- Blood pressure cuff

- ECG or electrocardiogram

These three things provide continous essential information throughout the operation about how the patient is feeling, how well their vital organs are working and how deeply asleep they are. One of the skills required of the anaesthetist is being able to interpret what the numbers mean in any given scenario, and what they need to do about it.

Is the blood pressure low because the heart isn’t pumping properly or is it because the anaesthetic drugs have made all of the blood vessels relax?

Is the oxygen level actually low or is it electronic interference from the surgeon’s cauterising forceps?

High airway pressures, low blood pressure, high heart rate and low oxygen suggests anaphylaxis until proven otherwise

Induction of anaesthesia

I like to draw comparisons between anaesthesia and flying a plane. The generally more interesting bits are during take-off and landing (induction and emergence from anaesthesia), and ideally there are only minor adjustments to be made during the surgery in between.

Induction of anaesthesia is like take-off.

After inserting a cannula into a vein in the hand or arm, the patient is given pure oxygen to breathe through a mask, to replace all the air (which is mostly nitrogen) in their lungs with oxygen. This acts as a reservoir of oxygen for the body to use throughout the period of time when they are not breathing during the intubation. It is an important safety net in case anything unexpected happens and we are unable to move gas in and out of the patient’s lungs – such as in the case of an unexpectedly difficult intubation.

Once the lungs are full of oxygen, the induction drugs are injected into the cannula and the patient goes to sleep. Once asleep, the muscle relaxant is injected and a timer started. The patient rapidly stops breathing, as their muscles become paralysed, and therefore starts using up the reservoir of oxygen sitting in their lungs. After about ninety seconds the patient’s vocal cords will be adequately relaxed to allow intubation, so the mask is removed and the laryngoscope is used to insert an endotracheal tube into the patient’s trachea.

MAC stands for Macintosh, the standard shape of laryngoscope used in adults. This is a size 4, which is generally used for taller patients

This usually takes less than a minute when uncomplicated, but occasionally there are surprises so it’s important that we have a few back up plans up our sleeve!

The operation

The aim of the game for the anaesthetist during the operation is smooth sailing, with a nice steady blood pressure, oxygen level and heart rate. Many surgical operations involve particularly painful or physiologically stressful parts that the body can react to even in the patient isn’t aware of it, which need careful navigation to avoid upsetting the body’s delicate balance and causing unnecessary spikes in blood pressure or heart rate.

The patient needs to be kept adequately asleep with enough pain relief on board to reduce the stress of the surgery itself. In the same way that a person who is asleep might unconsciously move their hand to swat away the fly that just landed on their nose, a patient under general anaesthesia won’t be aware of what is happening, however their body will still show a stress response to a painful stimulus if they’re not given enough pain relief.

For a simple, lower risk operation this often doesn’t involve actively doing much at all, which is how anaesthetists have become famous for their crossword and sudoku habits, however their job is to remain vigilant to change, and to ensure that they spot anything going wrong and to deal with it before it becomes an issue.

It’s very rewarding to hear the surgeon exclaim ‘they’re much more stable than I expected’ from the other side of the drape, unaware that it’s because you’ve been quietly correcting every possible physiological derangement before it became clinically apparent.

Extubation

As the surgeon ties the final few sutures, it’s time to get ready for landing, or extubation. The easy bit is switching off the anaesthesia, because the patient does all the work of waking up by breathing out the anaesthetic gas or metabolising and excreting the anaesthetic drugs, depending on what you’ve been using to keep them asleep. The tricky bit is keeping them safe as they ascend through the planes of anaesthesia, some of which can be rather turbulent to say the least.

However much like a plane descending through stormy clouds, the patient must rise through a dangerous middle zone of being semi-anaesthetised, where they can become agitated if not managed correctly, and in the worst case can either go into bronchospasm or stop breathing entirely. Clearly, this could be disastrous if the patient’s oxygen level were to drop to a dangerously low level, so we do our best to avoid these problems in the first place.

The key is ensuring you’ve suctioned out any saliva and secretions that might irritate the vocal cords when the tube comes out, reversed the muscle paralysis to ensure they have the muscle power to breathe effectively, and allow them to transition through this bumpy period relatively undisturbed.

Then, once they are awake enough to protect their own airway and breathe for themselves, the tube is taken out. Often the patient will still have strong pain relief and residual anaesthetic on board, and are exhausted from the stress of the operation as well, so they frequently will go back into a more normal version of sleep.

Recovery

While the hardest part is now over for the patient and the anaesthetic team, they’re still not safe to go back to the ward just yet, as the powerful drugs given during induction and throughout the operation will still be swilling around in their blood, and can still have dangerously sedating effects if the patient isn’t monitored appropriately. They are therefore looked after by a specialised recovery nurse in the recovery unit, where they are closely observed and their pain controlled with more strong drugs if needed while the last of the anaesthetic agent is excreted from the body. After handing over to the recovery staff, the anaesthetist usually says farewell to the patient at this point, and heads back to theatre to get ready for the next case!

We hope you have found this article useful, please fire away with any questions or comments, and check out our TikTok channel and podcasts for more content like this.