Transfers

Take home messages

- Treat a transfer with the same respect as a high risk laparotomy

- Treat a transfer from Resus to ITU the same as a trip in an ambulance

- Use a transfer checklist app such as STrApp, and a transfer record to document

It's go time

"Hi guys, thanks for coming, this is Mark. He's bumped his head and needs to go to St. Neuro's for haematoma evacuation asap."

"No trouble, happy to help."

"How much oxygen have you guys got in your truck?"

"Loads mate, more than you'll need."

"And you have enough fuel?"

"Full tank of diesel lad."

When you think about it, an ambulance is a bomb on wheels.

So it will come as little surprise that putting your critically ill patient in the back of one and carting them at supra-normal velocity through traffic across the country carries an element of risk.

The transfer deserves your respect.

You need to think of it as a procedure in its own right - one that carries risks, benefits and complications - and this has to help guide your decision as to whether it's the right thing to do at all.

This article is going to focus more on the interhospital transfer than intrahospital, but the principles are exactly the same - whether it's a corridor or the M4.

ACCEPT

This is a mnemonic that is often used for preparing to transfer a patient:

- Assessment

- Control

- Communication

- Evaluation

- Prepare and package

- Transport

Assessment

- What is wrong with the patient, and what do they need?

- Where do they need to be in order to achieve this?

- Is there the infrastructure and staffing available to facilitate this?

Control and communication

- Who's running the scenario?

- Who has ownership of the patient, and who else needs to be involved?

- Who needs to be aware of what's going on?

- What do the relatives understand?

Evaluation

- What level care is required?

- How urgently does this need to happen?

- Where and when should further resuscitation be carried out?

- Who needs to be with the patient? (SHO, registrar, consultant)

Prepare and package

- Patient

- Equipment

- People (you, nurse, paramedic, ambulance crew, relative)

Transport

Primary transfers are from somewhere in the wild (patient's home, street) to a hospital.

Secondary transfers are from one hospital to another, and are categorised based on the reason for the transfer.

The first three are of direct benefit for the patient.

1 - Urgent specialist support or investigation

- e.g. time critical neurosurgery

2 - Transfer for organ support not available at current location

- e.g. renal replacement therapy

3 - Repatriation closer to patient's home

- e.g. return to UK from abroad

4 - Capacity transfer

- e.g. due to lack of available critical care beds

Understandably we are trying to avoid category 4 transfers where possible.

How to choose how to travel

There are essentially two options here - road or air.

Air can be a helicopter, or a fixed wing plane for longer distances, or a hovercraft if a helicopter is just too quiet, convenient and fuel efficient.

Things to think about:

- How urgently the patient needs to move

- How far there is to go

- Whether altitude is going to make the patient more ill

- How much staff and equipment is required

- Road conditions and whether there are any

- Weather conditions

If it's absolutely steaming it sideways with hailstones, the patient has pneumocephalus and dilated bowel loops and you need to bring a relative with you - avoid the helicopter.

The Six Ps of Preparation

Your job as the anaesthetist accompanying the patient in the ambulance is simple.

You just need to think of as many things that could go wrong as possible, and then do something to prevent that terrible thing from happening.

Then be ready to manage that terrible thing if it happens anyway.

Easy.

A speed bump could knock the tube out.

- Tape, tie and double tie the tube

- Make sure you have all the necessary kit (and drugs) to put the tube back in, should it fall out

The ventilator could fall on the floor and break.

- Check and double check the ventilator, bring a bag valve set with you

The cannula might get pulled out.

- Make sure you have at least two good cannulas sited, and attach extension lines that will allow you to give meds without getting up

- Many of your drugs can be used IM or IO in a dire emergency

You might run out of sedation.

- If your ambulance breaks down and it's an hour to get recovered, have you got enough propofol, ketamine or midaz?

- Check your sedation, bring at least double what you'll need

- Your absolute worst case solution is weaning available sedation down to slightly-above-anxiolysis levels and keeping the patient still with roc

It's cold outside.

- Wrap the patient up, with blankets under the straps, and then more blankets on top

- Layers, layers layers

I might have questions.

- Confirm who, and where, your boss is at your home hospital

- Confirm who you're taking the patient to

- Make sure you have everyone's phone number

- Ensure your phone is charged

There might be a power failure.

- Ensure all of your equipment is fully charged

- You can keep a patient asleep and alive with a syringe and a BVM if needed

You get the idea - if you can conceive of something going wrong, you need to have an answer, or know where to find one.

The A to T transfer checklist

If you use this every time, you won't miss anything important.

- Airway

- Breathing

- Circulation - pressors and BP control?

- Disability/neuro - enough sedation?

- Exposure and access - at least two good IV access points

- Fluids - well-filled patients travel much better

- Glucose

- Haematology - blood, tranexamic acid?

- Infection - antibiotics?

- Just in cases (emergency drugs)

- K - potassium

- Last ABG

- Myself - phone, food, money, jacket, insurance?

- Notes - photocopied

- Oxygen - take at least double what you think you need

- Phone calls - do I need to call anyone else before we leave

- Questions - anyone on the team have any remaining queries?

- Rocuronium - when was the last dose, and do I have enough?

- Suction

- Toilet - go now

If you'd like to know how long your oxygen is going to last, check out these useful tables.

How to calculate oxygen requirement

- The patient will use some

- The ventilator will also use some

The patient will use (Tidal volume x Resp rate x FiO2) litres per minute.

The ventilator will usually have a set consumption rate, such as 0.5 litres per minute.

Total requirement: (Patient L/min + Ventilator L/min) x estimated duration of journey.

Then double it.

Then add a fudge factor of however much you want.

That's how much you need.

Usually this is less than the 2000 litres that most ambulances have on board these days.

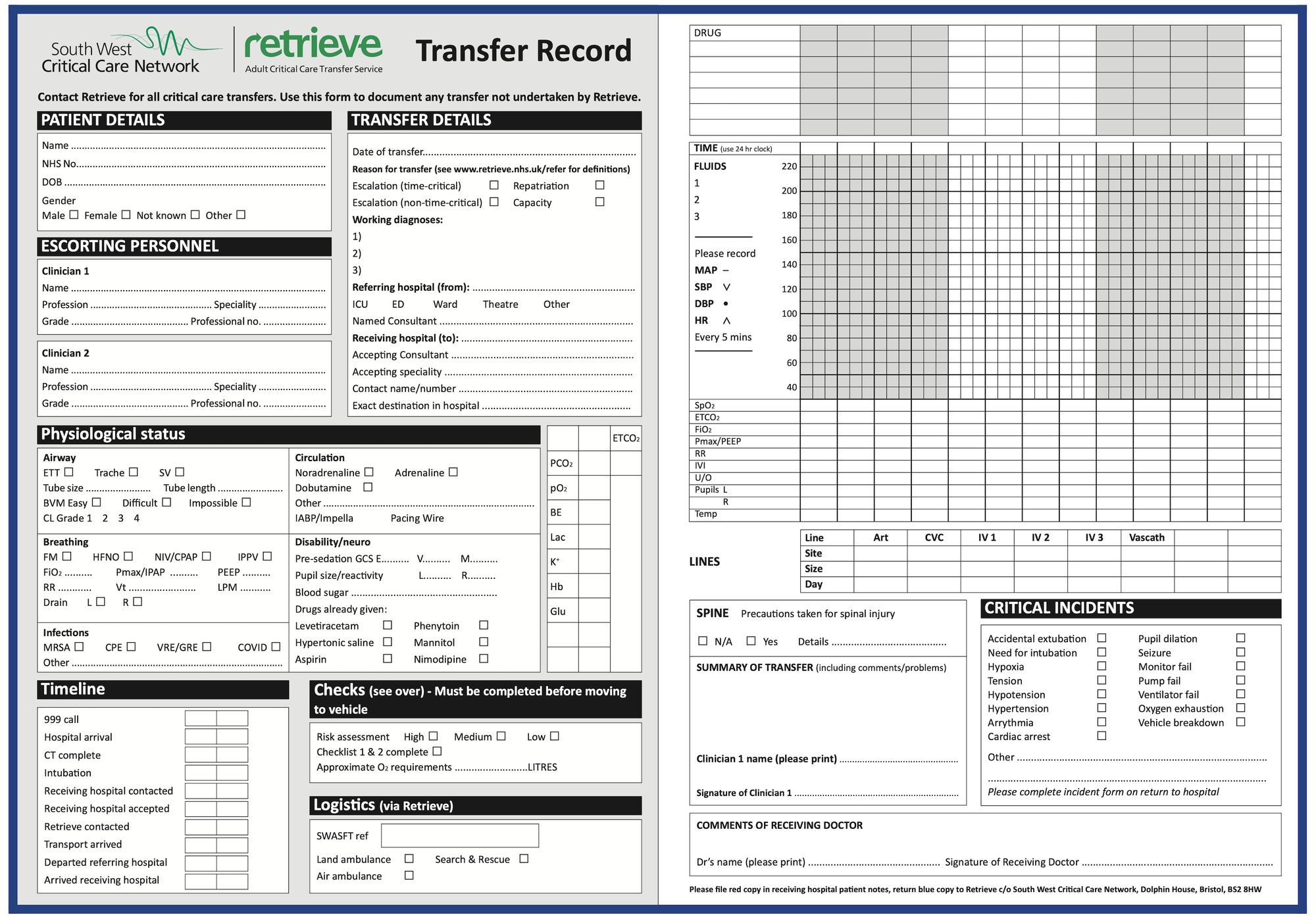

Documentation in transit

You can't just sit there and enjoy the nee-naws as you plough up the hard shoulder of a gridlocked motorway - you actually have to do stuff.

One of these things is keeping a record of what happened so that each fifteen minutes or so from start to finish is accounted for.

To make this easier, most transfer services and hospitals have some variation of this:

It's entirely self explanatory and helps you at the other end when handing over to the receiving team.

If you're really lucky you'll have an ICU or ED nurse with you who can help with documenting the observations on the move.

I like to move it move it

That's nice, but your patient doesn't, and neither does your monitor.

The combination of the average UK road surface and ambulance suspension makes for a queasy ride at best, and your equipment was not designed with speed bumps in mind.

Every time the driver brakes, blood rushes to the head, and every acceleration sends blood surging down the arm to the arterial line. Meanwhile the blood pressure cuff won't give a reading because the patient's leaning on it.

This means you get a lot of artefact in your monitoring signals.

- It helps to have a feel for what your patient's parameters are doing before you get in the truck - have they been rock solid or a bit wobbly already?

- If you're able to, whack an arterial line in before you go, so you can at least verify any dodgy blood pressure readings with another measurement technique

- Ensure your monitoring is firmly held in place, ideally your monitor should be clipped into a purpose-build bracket on the transfer trolley

- A lost ECG lead is more important in a cardiac patient fifty minutes from your destination than a time-critical neurosurgery patient as you're pulling into the car park - use your judgement

When things go wrong

The 'How bad is it if it crashes?' list, in descending order of badness, looks like this:

- Driver

- Patient

- Phone

The Driver

Those blessed with the skills and necessary qualifications to drive a six tonne bomb-on-wheels through red lights at night in the rain deserve a decent heap of respect.

In return, they will respect your skillset and expertise, and so if you say go as fast as possible, then they may just do exactly that.

Aim for smooth rather than land speed record.

While it is the driver's responsibility to ensure they're safe to transfer the patient, it doesn't hurt to double check they've had enough caffeine, sugar and been to the loo recently enough to make the journey more manageable.

Wear your seatbelt and do as you're told.

Patient

Stuff goes wrong, that's why you're here.

The first task is to spot that there's an issue.

- Usually an alarm goes off

- You need to decide if this is a machine error, or a patient problem

Then you have to decide if you need to do anything about it, and how urgently.

- If the sats have dropped just a bit, then maybe trying just putting the FiO2 up a notch

- If the sats have suddenly dropped a whole lot - you need to think about pulling over

Are you fixing on the move, pulling over or diverting to the nearest ED?

This question is immensely nuanced, and different anaesthetists might do different things with the same scenario.

Some examples include:

- Cardiac arrest - pull over and start ALS on the roadside

- Tension pneumothorax two hours from destination hospital - needle decompression and divert to nearest ED for chest drain

- Bradycardia and hypertension in time critical neurosurgical patient - run 3% saline in and keep going

You usually have time to phone your boss for advice, and have them on speakerphone while you fix bigger problems that you're uncomfortable with.

Phone

Portable battery packs are ridiculously useful and not nearly as expensive as they used to be.

Given we use our phones for everything from communication to drug dosing to checking the latest guidelines - you kinda need to keep it topped up.

Write important phone numbers on a piece of paper.

If someone dies in transit

As far as 'things anaesthetists have nightmares about' go, this one's up there.

We've already discussed how we'd all really rather not be in the back of a truck when a patient crashes, but it's even more true if that isn't a reversible process.

Morbid and paranoid as it sounds, I personally always ask my consultant 'If this patient dies in the ambulance, do we turn back or keep going?'.

The response is usually a startled look and recognition of a thought-not-yet-considered, but it usually opens up a useful dialogue.

Go through the motions

You know you can do ALS, and you can manage an airway, so you and your green-suited friends can give this patient as good a chance as any at recovering, so give them your best.

Pull over as soon as is safe to do so, start CPR and airway management as you would, and get your boss on the phone for advice.

Unless of course there is specific paperwork in place determining that CPR would be inappropriate, even during transit.

An example would be a known ruptured aortic aneurysm being transferred for surgery - if there is sudden abdominal pain followed by a rapid drop in blood pressure and consciousness, then CPR is unlikely to fix much - but discuss this with your boss before leaving where possible.

If the patient happens to pass despite your best efforts, then think about doing the following:

- Inform your consultant and the receiving team right away of what has happened (ideally while CPR ongoing), and ask them what to do next and where to go

- Write down what you can remember as soon as you possible can, and in as much detail as possible

- Work with your equally traumatised colleagues in green to get the patient to where they now need to be

- Discuss with your boss and the receiving team about informing next of kin - this should be a consultant conversation, not an exhausted and traumatised SHO/Registrar one

- Get yourself back to your home hospital safely, and then debrief with your consultant

- Be kind to yourself - It almost certainly isn't your 'fault' - the patient was critically ill enough to need moving to an entirely different hospital - so they were already at considerable risk

- By all means think about what you could have done differently to improve, but sometimes these things just happen

Do not suffer in silence - speak to colleagues, family, friends, TRiM practitioners about your experience.

You can also talk to us - we're always here to listen and offer what advice we can - ping us an email at anaestheasier@gmail.com.

On a happier note

If you take the patient on your hospital's ICU transfer trolley, the crew are obligated to bring you home, so you won't be left trying to hail a cab holding a ventilator and a tray full of questionable chemicals.

Here's our other post on our top tips for transfers.

Syllabus

- Describes the requirements for safe transfer of patients with brain injury

- Demonstrates the ability to resuscitate, stabilise and transfer safely patients with brain injury

- Outline the principles of safe inter-hospital transfer of the resuscitated patient

- Explains the risks/benefits of Interhospital patient transfer

- Explains the concept of primary/secondary/tertiary transfer

- Outlines the hazards associated with Interhospital transfer, including but not limited to physical, psychological and organisational

- Describes the increased risks to critically ill patients of transfer and the reasons for these risks

- Outlines strategies to minimise risk during Interhospital transfer, including but not limited to: Stabilisation, Pre-emptive intervention, Sedation, Monitoring, Packaging, Choice of mode of transfer

- Explains how critical illness affects the risk of transfer

- Explains how time-critical elements may influence risks to the patient and transfer personnel and how these should be managed to reduce them

- Understands the increased risk of interventions during Interhospital transfer

- Outlines the specific considerations for transfer of patients with specific clinical conditions, including but not limited to: o head, spinal, thoracic and pelvic injuries o critically ill medical patients o burns o children o pregnant women

- Lists and explains the critical care equipment used during transfer including but not exclusively: • Ventilators • Infusion pumps • Monitoring Lists the different modes of ventilation and explains the selection of appropriate parameters in e.g. Asthma/COPD and ARDS

- Outlines the different modes of transport available for inter-hospital transfer, including risks/benefits

- Understand the safety implications of electrical and hydraulic equipment that may be used during patient transfer

- Recalls/describes the physiological effects of transport including the effects of acceleration and deceleration, including Newton’s laws of motion

- Understands the effects of high ambient noise on patients and alarm status

- Recalls/discusses the reasons for patients becoming unstable during transfer and strategies for management

- Recalls/describes how to manage patients who develop sudden airway difficulties whilst in transit [both in the intubated and un-intubated patient]

- Outlines the ethical issues related to patient transfer, including the need to brief patients and their relatives

- Awareness of the laws relating to deaths in transit

- Outlines how to find and use the national register of critical care beds

- Outlines the regional protocols for organising transfers between units

- Outlines the importance of maintaining communications between the transfer team and the base/receiving units

- Outlines the roles and responsibilities of all staff accompanying the patient during transfer including the ambulance technicians and paramedics

- Describes the personal equipment needed when leading a transfer, especially when a prolonged journey is anticipated

- Discusses the importance of auditing practice and reporting critical incidents that arise during Interhospital transfer and the need for appropriate research

- Demonstrates ability to determine when patients are in their optimum clinical condition for transfer

- Demonstrates the ability to optimally package a patient for Interhospital transfer to minimise risks

- Demonstrates the ability to establish appropriate ventilation and monitoring required of a critically ill patient for interhospital transfer

- Demonstrates the ability to safely sedate a patient for interhospital transfer

- Demonstrates ability to know when the patient’s needs exceed the local resources available/that specific expertise is required

- Demonstrates the need to integrate patient diagnosis with the physiological effects of transport

- Demonstrates the ability to manage sudden loss of airway control, vascular access and monitoring in patients during transfer

- Demonstrates the necessary organisational and communication skills in managing inter-hospital transfers safely and effectively, recognising the importance of maintaining contact with base/receiving units if necessary whilst on transfer

- Demonstrates appropriate situational awareness

Useful resources

This is an unbelievably high yield document

Here's a great podcast

Here's a brilliant app

Here's FICM's own guidance

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.