Major Obstetric Haemorrhage

Podcast Episode

Take home messages

- Major obstetric haemorrhage is the leading cause of global maternal morbidity and mortality

- The uterus returns around 500ml of blood to the maternal circulation after delivery

- Uterotonics are the mainstay of pharmacological therapy

It's not complex

While major obstetric haemorrhage is certainly up there on the list of 'things I'd rather not have to manage alone on a weekend night shift', it's definitely one of the simpler cases - physiologically speaking:

- blood has fallen out

- you need to put it back

- and help stop any more falling out

Simples.

It's also not easy

- You started with one patient

- and now you have two

- and the patient is having major abdominal surgery

- with life-threatening bleeding

- and they're awake

- and their partner is watching

Ah.

Not quite so 'simples' any more.

The challenge with managing major haemorrhage in obstetric anaesthesia largely lies in the logistics department, with communication, people management and anticipation being the most important skills that will see you, and the patient, through this ordeal.

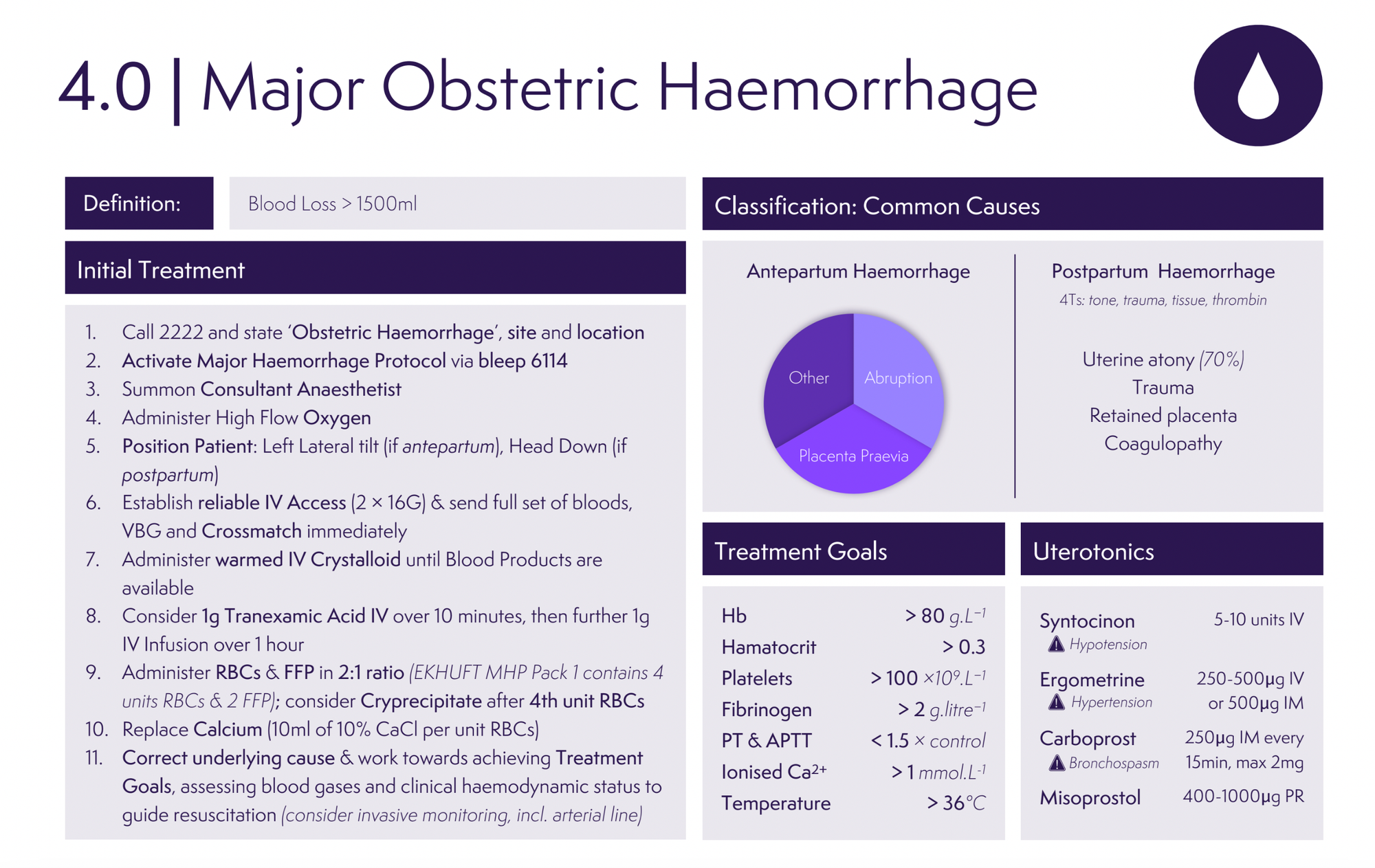

This whole post in a nutshell

- Anticipate blood loss (big IV access, antepartum risk factors, crossmatch and cell salvage)

- Recognise blood loss (watch the surgeon's hands, walk around the room, look at the operative site, communicate with the theatre team)

- Act early (activate the MOH call early, convert to GA, start effective resuscitation, call your consultant in)

- Replace what's lost (RBCs, clotting factors, platelets, calcium, and lots of uterotonics)

Pregnant blood is different

Consider for a moment the following:

- You have a very high flow, low resistance vascular system receiving upwards of 25% of the entire maternal cardiac output

- This is tightly intertwined with the baby's own vascular system in the placenta

- You're then ripping these two apart and expecting both humans to somehow survive

Evolution is rather clever, thankfully, and one of its many achievements is preparing the female human body for the inevitable blood loss of childbirth.

What haematological changes occur in pregnancy?

- Haemodilution, due to increased blood volume

- Reduced platelets

- Leukocytosis

- Prothrombotic state due to venous stasis and increase in clotting factors

As if on purpose, the pregnant body increases blood volume by around a litre, and dilutes down those precious erythrocytes, to allow the mother to sustain blood loss that would make a general surgeon's toes curl, without so much as batting an eyelid.

(Eyelid batting may be a sign of excessive blood loss.)

Remember this is a physiological anaemia and despite the lower concentration of platelets, the parturient is actually prothrombotic, which makes sense, because there is anticipation of blood loss during birth, and the body adapts to that by having more blood to spare, and fixing any bleeding more quickly.

Platelet production increases, but the platelet count decreases due to increased destruction and haemodilution occurring maximally in the third trimester.

Oh and just in case that wasn't enough, as the uterus squeezes down, around 500ml are returned fairly promptly to the maternal circulation.

How much is too much?

A bit of bleeding is okay, but as with all things there is a limit, and when you start heading north of a litre of blood loss, you start wanting to fix things rather rapidly.

It's notoriously difficult to accurately estimate exactly how much blood a mother has lost, apart from thinking 'that's quite a lot of blood'.

Add to this that a parturient has a higher resting heart rate and lower blood pressure than usual, which makes it even trickier to determine what constitutes clinically relevant bleeding.

Weighing swabs and inco pads, and using kidney dishes are both sensible methods of quantifying blood loss, but in general we still tend to underestimate just how much has been spilled.

Let's pause for a few definitions.

Antepartum haemorrhage

- From 24 weeks' gestation onwards

- 3% to 5% of all pregnancies

- Spotting – staining, streaking or blood spotting noted on underwear or sanitary protection

- Minor haemorrhage – blood loss less than 50 ml that has settled

- Major haemorrhage – blood loss of 50–1000 ml, with no signs of clinical shock

- Massive haemorrhage – blood loss greater than 1000 ml and/or signs of clinical shock

Yes - 50ml - we double checked.

As per RCOG guidelines

Postpartum haemorrhage

- Primary PPH is <24 hours after delivery

- Secondary PPH is 24 hours to 12 weeks after delivery

- Minor PPH is defined by RCOG as 500ml - 1000ml

- Major PPH is defined as 1000ml - 2000ml

- Severe PPH is >2000ml

Causes of APH

- Placental abruption - 33%

- Placenta praevia - 33%

- Uterine rupture

- Cervix/vagina/vulval bleeding

Often no cause is identified.

Causes of PPH

Primary PPH

- Atony - 80%

- Trauma

- Coagulopathy

- Retained placental tissue (including placenta accreta/increta/percreta)

- Uterine inversion

Secondary PPH

- Endometritis

- Retained products of conception

What to do

Do exactly what you always do, you brilliant, level-headed rock of reassurance in the chaotic surgical seas of panic and turmoil:

- Stay calm (or at least swan like a boss)

You've got a petrified patient, a panicking partner, a perturbed surgeon, a perplexed midwife and a powerhouse of an ODP/Anaesthetic nurse to help you absolutely smash this, so take a deep breath and crack on.

Then work through the following three blocks

Block 1 - Initiation

- Call for assistance as required

- Start with airway and breathing

- Whack on some high flow oxygen

- Make sure you've got big access, and double it or make it bigger

- Activate the major haemorrhage protocol

- Warmed fluid bolus only if their blood pressure needs it

Block 2 - Resuscitation

- Decide if you need to convert to GA*, and if in doubt, remember rule 3

- Start blood product resuscitation in a 1:1:1 ratio

- Don't forget fibrinogen

- Keep the patient warm

- Tranexamic acid

- Cell salvage

- It's art line time

*Don't forget to hyperventilate slightly to achieve a low-normal ETCO2 to reflect the physiological hyperventilation in pregnancy.

Block 3 - Reassess and refine

- Send bloods for FBC, Coag screen, LFT and U+E and crossmatch at least four units

- Blood gas analysis*

- Point of care viscoelastic assays (ROTEM/TEG) are very useful if available

- Give 10ml 10% calcium for every 4 units of packed red cells

*Remember that haemoglobin concentration takes time to drop after acute blood loss, so a normal value is not reassuring.

Have three big questions in your head throughout

- Is this major haemorrhage?

- Is my resuscitation working?

- Are we heading towards DIC?

Smart resuscitation is constantly reassessing, adapting and anticipating what is required next, so don't just throw a bunch of blood products in and hope for the best.

What are the biochemical targets for managing major obstetric haemorrhage?

- Platelets >50-75

- PT ratio less than 1.5

- Fibrinogen greater than 2

- Calcium greater than (ionised 1)

- Temperature greater than 36

- Haemoglobin greater than 70

You need to be actively asking yourself these three questions on a regular basis and satisfying yourself that either fixing it, or calling for more help.

Examples of 'more help'

- More theatre staff to help with checking and administering blood products

- Another anaesthetist, ideally more senior than yourself, to help out

- Your consultant, who should at least be aware of a major obstetric haemorrhage, and most likely will want to be directly involved

- Haematology, for guiding ongoing resuscitation

- Interventional radiology, for stopping bleeding

- Other surgeons, if the bleeding is coming from somewhere else

- Intensive care unit

- ECMO if you have it immediately available*

*Very last resort

What interventions can be used to control haemorrhage?

- Bimanual uterine compression

- Intrauterine balloon catheter (Bakri, Rusch, Foley)

- Haemostatic compression sutures

- Uterine artery ligation

- Aortic cross-clamping

- IR-guided uterine artery embolisation

- Peripartum hysterectomy

Tone is important

Whether it's your sats beep, your surgeon's voice, or the patient's recently vacated uterus - tone is important.

Active management of the third stage of labour reduces PPH by 70%, and consists of:

- Controlled cord traction

- Early cord clamping

- Uterotonics

However there is a trend toward delayed cord clamping as it is beneficial for baby, and controlled cord traction only really helps if the third stage is delayed, so basically it's just uterotonics that make a major difference.

Bear in mind that at C-section, the uterus has not undergone the normal physiological contraction process, and has instead been sliced open with a very un-physiological scalpel, and you can see why getting the uterus to contract effectively is of paramount importance.

How to manage uterine atony

- Oxytocin - 5 units slow IV after delivery then 10 units/hr infusion for 4 hours*

- Carbetocin - up to 100μg at delivery (no infusion required as lasts 5 times longer than oxytocin)

- Misoprostol - 400-600μg PO/PR/PV

- Haemabate (carboprost) - 250μg IM every 15min up to 2mg

- Ergometrine - 200-500μg IM or cautious IV

*This is variable, with some sources recommending 3 units followed by 2.5-7.5 units per hour - it depends on where you work.

Jehovah's witnesses

Genesis 9:4, Leviticus 17:10, and Acts 15:29 all forbid human consumption of blood in any form.

The majority of patients will accept a blood transfusion when necessary.

There are a subset of patients that won’t accept a transfusion for whatever reason, and they need to be properly consented to explore their options and fully clarify the conditions upon which they will refuse a transfusion. Some patients will accept it if it's a matter of life or death, while others will not accept it under any circumstances whatsoever, so the key is thorough discussion and accurate documentation.

Some Jehovah’s witness patients will accept cell salvage, and others will refuse it on the grounds that the blood has left their body, and therefore should not be reintroduced to their system.

I have seen a case where the patient accepted cell salvage, so long as there was continuous column of fluid connecting her to the blood, so she could justify to herself it never really left her body, so by running saline through the machine first and connecting it to the cannula, she was then happy for us to use it, and she ended up requiring 500ml of her own blood back.

If you'd like more

Useful Resources

From our colleagues at FRCA Revision

Here are the RCOG green top guidelines

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.