Do Not Resuscitate

DNAR forms, or ‘Do not attempt resuscitation’ forms have received a lot of attention in the media recently, particularly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As you might expect, they have stirred up rather a lot of controversy regarding how they are used, when they are appropriate and who should be making the relevant decisions involved. This is entirely understandable given the extremely emotive issue they discuss, and the potential harm if used incorrectly. In this post we will cover what they actually mean, when and why they are used, and what they are trying to achieve, hopefully clearing a few of these issues up in the process.

Cardiac Arrest

If you are in hospital and your heart stops, for whatever reason, then by definition you are in ‘cardiac arrest’ and in this situation hospital staff are trained to start CPR, or ‘cardio-pulmonary resuscitation’, in order to try and get it started again.

The idea is simple – squeeze the heart to pump the blood – but the procedure is brutal – powerful compressions applied to the middle of the chest, squeezing the heart between the breastbone and spine, cracking ribs and bruising lungs in the process.

Hospital staff will do this unless there is a valid instruction in place not to do so, (i.e. a DNAR form). The decision to start CPR has to be very quick, automatic almost, because time is of the essence; as soon as your heart stops your vital organs – particularly your brain – are being starved of oxygen and are therefore rapidly becoming irreversibly damaged. Most organs can be transplanted or replaced, but not the brain, and the brain does not cope well with no blood supply.

The aim of CPR is to push blood and oxygen around the body to slow down the damage to the vital organs and buy the medical team time to try and fix the cause of the cardiac arrest. Apart from in very exceptional circumstances, sternal compressions are nowhere near as effective at moving blood and oxygen around the body as the hearts own compressions.

This is the key, CPR does not actually fix anything, all it does is buy time, and not very much at that.

Reversible Causes

The key here is understanding whether the cause of the cardiac arrest is ‘reversible’ – that is, can you fix it and get the person better again?

Sometimes this is obvious – if the heart has stopped because the entire organ has been forcibly removed from the body by an explosion, then most people would agree that this is not a reversible cause, and starting CPR on the poor person’s body would undoubtedly not work.

On the other hand, if a fit young person has been struck by lightning, and their (previously) perfectly healthy heart has flipped into a strange rhythm and stopped pumping effectively due to the electric shock, then this is almost certainly reversible with a defibrillator, and CPR is absolutely appropriate and actually quite likely to work.

So how do you know whether the cause is reversible, when somebody has a cardiac arrest in hospital? You can’t know for sure, but it is widely agreed that there are essentially only eight causes that we can treat, and we call them the

‘Four H’s and Four T’s’

So we aim to treat all of these during the resuscitation attempt, while doing CPR and giving electric shocks where indicated, and then we know that if it doesn’t work, then it likely isn’t a reversible cause.

The eight reversible causes of cardiac arrest

Hypoxia

Lack of oxygen causes the heart muscle to stop contracting- for example choking or suffocating.

Hypovolaemia

Not enough blood to supply oxygen to the heart – severe bleeding or severe dehydration.

Hypothermia

Heart too cold to pump blood effectively – very rare – not usually seen in hospital.

Hyper or Hypokalaemia

Potassium levels too high or too low – disrupts the electrical signals in the heart and upsets its rhythm. This also covers other electrolytes like calcium and sodium, all of which should be normalised during the resuscitation attempt.

Toxins

Cardiac arrest due to a specific poison or drug overdose. Rare in hospital, but does include overdoses of prescribed medications given in error.

Tension pneumothorax

This is a rare form of collapsed lung in which pressure builds up outside the lung but inside the chest cavity, compressing the lungs and heart and rendering it unable to refill after contracting, preventing it from effectively pumping blood around the body.

Tamponade

The heart sits in a rigid bag called the pericardial sac. If blood or another fluid rapidly accumulates in this sac, then it compresses the heart itself, preventing the heart from refilling properly and causing it to stop beating.

Thrombus

A blood clot, either in the lung or one of the major vessels to the heart, causing a blockage to blood flow and a lack of oxygen supply to the heart muscle, resulting in cardiac arrest.

Advanced Life Support

Once someone has been identified as being in cardiac arrest, there is a set algorithm defined by the Resus Council here, which hospital staff will follow, while the crash team try and work out if any of the above are causing the cardiac arrest.

If one of the above problems is identified, then treatment is started while CPR is ongoing, to see if by treating the cause it’s possible to get the heart started again.

Sometimes it does

But much more often than not there is too much damage done already for the body to recover.

This is especially the case for hypoxia (lack of oxygen) as the heart is so resilient that it will keep going, using whatever fuels it can get its hands on, right until the bitter end. So the body has to be profoundly low on oxygen for it to actually give up and stop.

By this time many of the other organs, particularly the sensitive brain, have already been severely damaged beyond repair.

Why not just give it a go?

Surely, if someone’s heart has stopped, they’ve essentially died, so it can’t get any worse right?

So why not just do CPR on everyone because it might just work?

This is understandably the stance that many people take, however there are several reasons why it is absolutely not appropriate for everyone to receive CPR when their heart stops:

Chest compressions are very traumatic

They cause broken ribs, punctured lungs, bruising and bleeding around the heart, and potentially damage to organs in the abdomen as well. Not to mention that the force of compressions also causes leakage of faeces, urine and vomit. If someone’s heart has stopped, and for whatever reason it is deemed extremely unlikely that CPR is going to work, then it is a horrible thing to do to someone when they die.

If my grandmother reaches the end of her natural life and passes away peacefully in hospital, with her family at her bedside, would I would want the medical team crashing in and doing that to her poor body?

Chest compressions are psychologically damaging

I remember the first time I performed CPR on a young man and he not only survived but recovered back to full health; it was one of the most thrilling and rewarding moments of my career.

However I also remember countless occasions where I have had to perform chest compressions on the bodies of over-80 year olds because they were inappropriately ‘still for resuscitation‘.

It is a feeling like no other; frail bones cracking beneath your hands as you try to pummel life back into a corpse, the lifeless eyes gazing as their body writhes and jumps with each jolt of the defibrillator. The psychological damage done to medical professionals by inappropriate CPR is widely underappreciated, equally the impact on the relatives and other patients in the ward who may bear witness to at least part of the resuscitative efforts is often forgotten.

It very rarely works

Remember that CPR is a form of medical treatment.

If I were to develop a drug with the success rate that CPR has, and tried presenting it to a pharmaceutical company, I’d be laughed out of the room.

It does not work well at all, especially when done inappropriately, and it should only be used upon the people who are likely to benefit from it. A full-blown resuscitation effort in hospital usually involves up to four or five nurses and health care assistants, three or four doctors, resuscitation officers and then porters running to get equipment.

Enormous amounts of non-reusable equipment such as defibrillator paddles, invasive airway equipment, blood test needles, and drugs such as adrenaline are also used up in the process, which may last up to an hour and a half in some cases.

Not only are all of those members of staff occupied and unable to help other patients during this time when they’re trying to resuscitate someone who has died, they’re then left physically exhausted and psychologically bruised in the aftermath.

There is a fate worse than death

This is the most important reason. (in my opinion)

Most people view CPR as a binary process – either it works or it doesn’t – and this is the reason why most people think it’s worth ‘giving it a go’ in everyone.

But this isn’t the case.

There is large and terrifying grey area in the middle that, if people were more aware of it, would almost certainly change the public opinion of DNAR forms. There are a great number of patients in whom CPR would be just effective enough to get the heart started again, but who would in the process suffer such catastrophic damage to their other organs that they would never be the same again.

In the mildest cases this could mean requiring dialysis for the rest of their life or a kidney transplant because their kidneys have failed due to the lack of oxygen during the cardiac arrest. In the most severe cases it could represent a living, breathing person who is unable to walk, talk, feed themselves or use the toilet and who may or may not be in constant pain, but can’t communicate that to the outside world.

These people need 24 hour care, every day, until they eventually die of something else. Usually this is caused by a painful, distressing infection either from aspirating food or from developing a pressure sore from lying in one position for too long. They become an enormous financial and emotional burden on their family, and friends who are now wracked with guilt for subjecting their loved one to a life they knew they would have never wanted, but with no way out from their suffering other than to wait for them to die of some other ‘natural cause’. This may sound dramatic but it’s true, and it’s something we see all the time on intensive care – patients who have ‘survived’ but not quite enough to live a life they would want.

When you go into the medical profession you vow not to do harm, and this feels a lot like doing harm.

So who should have CPR?

Very few people would argue that a heart transplant would be appropriate in a 94 year old man with heart disease, poorly controlled diabetes, kidney failure, emphysema and who can only walk a few paces with a zimmer frame before needing to sit down and catch his breath. The enormity of the operation, the stress on the already very weak and frail body, and the incredibly unlikely success rate of the procedure, let alone the lengthy and exhausting rehabilitation afterwards mean that it would be completely unfair to put that poor man through all the pain and suffering for what is almost certainly a very poor outcome.

Replace heart transplant with CPR, and the same applies.

There’s an elegant phrase which states ‘CPR works if the heart is the first organ to stop, not the last’.

If the heart has stopped in an otherwise fairly healthy person due to an unexpected heart attack, a trauma, electrocution, drug overdose, or any of the 4H’s and 4T’s, then with the right treatment it is possible to get things working again (Hence why we have the 4H’s and 4T’s!).

However if a person’s heart is not getting enough oxygen due to a chronic lung condition and the blood is being poisoned with waste products because of the patient’s kidney disease, and then they have an infection on top of that causing the heart to finally give out and stop, then the likelihood of fixing all of these things quickly enough (and sufficiently such that the person can enjoy a quality of life they would be happy with) is so low that you’re more likely to do them harm than any good at all.

So who makes the decision?

To cut a long story short, it is the medical team’s decision as to whether they feel that performing CPR would be in a patient’s best interests. However it should be a decision that is communicated properly to, and hopefully agreed with, the patient and their family, to ensure that everyone is on the same page should the worst happen. Legally, or ‘technically’ – however you want to phrase it – the family and patient do not have to agree for the form to be valid, however I very strongly believe that if a proper discussion is had, and the points I’ve made above are effectively communicated, then the family and patient are likely to agree with you if you feel CPR truly would be inappropriate.

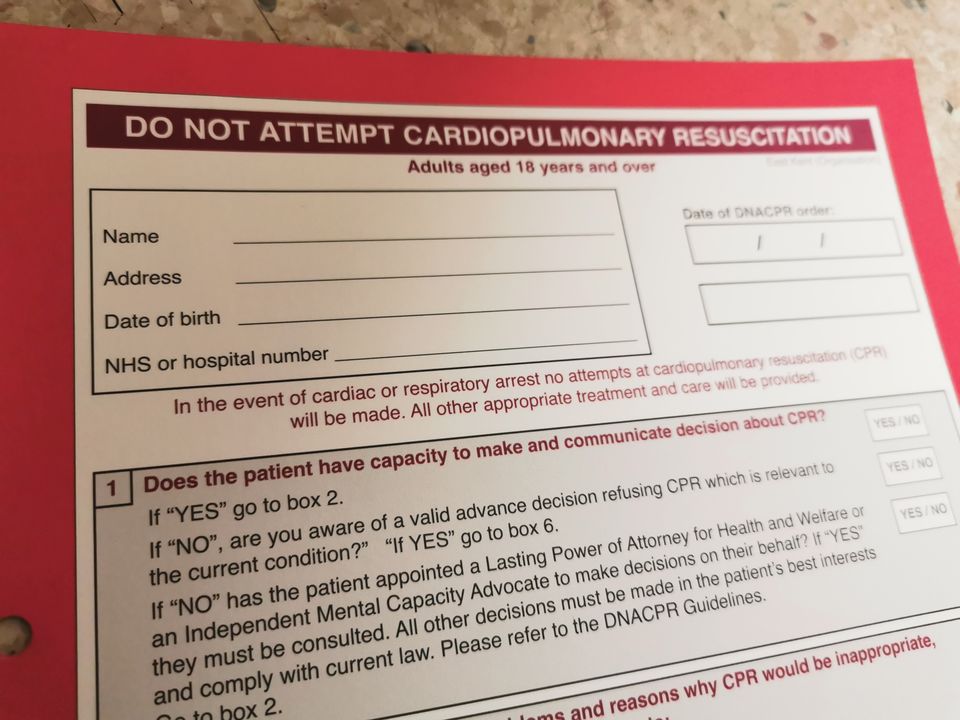

This is where the infamous DNAR Form comes in. This bright red form sits at the front of a patient’s notes and specifically states that should this person’s heart stop, then it would not be the right thing to start chest compressions. It has to be big and colourful and right at the front so that it can be found in a rush to avoid doing unnecessary harm to the poor patient.

It is easy to see how a DNAR form looks like a big ‘WE’RE GIVING UP ON YOU‘ symbol to those who don’t know exactly what it means, especially if they haven’t had a proper discussion about it. But it absolutely does not mean ‘withdrawal of treatment’ or denial of any sort of therapy. It only answers one question, which is

‘if this patient’s heart stops, should we put them through the horrible procedure of CPR?’

It’s not an easy discussion, especially given you’re usually trying to bring the subject up when a patient is already unwell and their relatives are desperately worried about them already – the last thing they want to think about is what happens if they die. This is why ideally these discussions should be had much earlier on, for example when a patient reaches a certain age or has multiple chronic illnesses that mean they would be unlikely to benefit from CPR, and to be fair to our enormously overworked GPs, many of them are doing this all the time, to protect their patients’ best interests.

*** VERY IMPORTANT CAVEAT ***

Outside of hospital, when you don’t know anything about the person or their medical background, and you do not have a DNAR form in front of you confirming this person is not for resuscitation, then of course the right thing to do is to start CPR. It is widely agreed that it is far worse to deny someone CPR who may benefit from it than it is to perform CPR on someone who won’t.

Hopefully this has given you some idea of what CPR is and what a DNAR form means and when it’s appropriate. The most important message that I’m trying to convey is that as medical professionals we always try to do what’s best for the patient in front of us, and if it seems like we’re being unfair or ‘denying’ a patient an opportunity or treatment – it’s because we’ve seen the horrors on the other side and are trying to protect them from unnecessary harm.