Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Take home messages

- DKA is a medical emergency with substantial morbidity and mortality

- Rehydration and a weight-dependent fixed rate insulin infusion are key

- Don't forget the potassium!

Sweet and Spicy

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) or 'the deeks' as literally nobody calls it, is one of our favourite conditions to treat, because when managed effectively the patients generally get much better very quickly indeed.

A comatose, acidotic and terrifyingly hyperglycaemic 20 year old can be sat up and chatting in a matter of hours, just as long as you spot it and sort it ASAP.

The diagnostic criteria

- Blood glucose >11.0 mmol/litre*

- Ketones ≥3.0 mmol/litre or ketonuria >2+

- pH <7.3 and/or Bicarbonate <15 mmol/litre

Not exactly tricky to see how diabetic keto acidosis gets its name.

*If the patient is known to be diabetic, and they're ketotic and acidotic, it's still DKA even if the sugar isn't above 11 (but it usually is).

What are the causes?

- Not enough insulin (usually a lack of administering it)

- Infection*

- New presentation of diabetes

- Trauma

- MI, stroke and any other significant stressor

*This can be due to some other pathology such as bowel perforation or appendicitis, which needs managing separately to DKA

Oh, and DKA can cause an acute abdomen all by itself, so it's nice to rule it out before anaesthetising someone for an unnecessary laparotomy.

What it looks like

Classically you're looking at a young and terribly dehydrated patient in varying states of consciousness.

They may be a 'repeat attender' or have never presented to hospital before.

These patients can present exceedingly unwell, and the vast majority of the morbidity and mortality is as a result of delay in presentation and diagnosis.

That's not to cast judgement over the poor patient, rather to reassure you as the medical practitioner that they can be very sick indeed when you first lay eyes on them, and that's out of your control.

Gently does it

DKA is often the first presentation of type I diabetes, and can be an incredibly distressing experience both physically and psychologically, especially for a young patient who's desperately unwell and never been in hospital before.

I usually start by asking "Do you take insulin?" as a way of probing whether the patient is aware of an existing diagnosis of Type I diabetes, before heading any further down the diabetes conversation.

It's not just Type I

Type II diabetic patients can get DKA, especially if they're usually on insulin.

Patients with Type II diabetes mellitus can present with DKA, however it is usually less severe in terms of acidosis and they usually have a more sensible potassium level when they present.

This is presumably because they're insulin resistant, and are still producing enough insulin to maintain more homeostatic ion levels and keep ketone production under at least some control.

What happens

There's not enough functioning insulin, either due to an absolute deficiency (Type I) or relative deficiency as a result of insulin resistance (Type II).

- There's also relatively too much catabolic stuff hanging around - glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone and catecholamines - often as a stress response to an infection, MI, bowel perforation or what have you

- This leads to hyperglycaemia as the blood sugar that has been absorbed from the gut, and released via gluconeogensis and glycogenolysis by the above catabolic hormones, cannot be taken up into the tissues and utilised

- To compensate, the body starts using free fatty acids

- These are oxidised in the liver to ketone bodies

- These ketones are acids, that then dissociate and release hydrogen ions, causing acidosis

What are the three ketone bodies?

- Acetone

- Acetoacetate

- 3-β-hydroxybutyrate (this is the main one in DKA)

Death by osmosis

The metabolic ketoacidosis is bad, but patients can compensate at least to some degree using their lungs.

As you'll remember flawlessly from medical school, Kussmaul breathing is a characteristic, regular deep sighing designed to offload as much CO2 as possible in an attempt to correct an underlying metabolic acidosis.

The big issue is the profound osmotic effect and dehydration that results from the raging hyperglycaemia.

- Hyperglycaemia drags fluid out of the intracellular compartment

- The glomerulus filters out all the sugar, but the nephron can't reabsorb it all

- This drags fluid into the urine, causing an osmotic diuresis

- This leads to depletion of potassium, phosphate and sodium, as well as catastrophic dehydration

Investigations to do

To diagnose it

- Blood glucose

- Blood ketones

- Blood gas - for pH and bicarbonate (lactate is helpful too)

To look for causes

- Full blood count

- Urea, electrolytes and creatinine

- LFTs

- CRP

- Amylase

- Pregnancy test where relevant

- ECG

- Blood cultures

- Scans and things where clinically indicated

To monitor progress

- Blood sugar

- Blood ketones

- Blood gas

- Potassium - your insulin therapy is going to drive potassium way down, and you're going to need to replace it fairly thoroughly

How to treat it

ABC

You chose this career because ABC is your favourite thing apart from 3am cannula requests for geriatric vancomycin.

- Airway protection if vomiting, coma, seizing, the usual

- Ventilatory support if inadequate CO2 clearance or exhaustion, or pneumonia which is causing the DKA in the first place, you get the idea

- Fluid resuscitation, catheter to measure ins and outs

- Metabolic management - fluids, insulin, potassium, glucose

- Find and treat the cause - blood cultures and low threshold for antibiotics

Follow the protocol

I promise your hospital has a DKA protocol. If you can't find it, google 'DKA protocol NHS' and you'll find at least eight neighbouring NHS trusts' own versions of exactly the same idea.

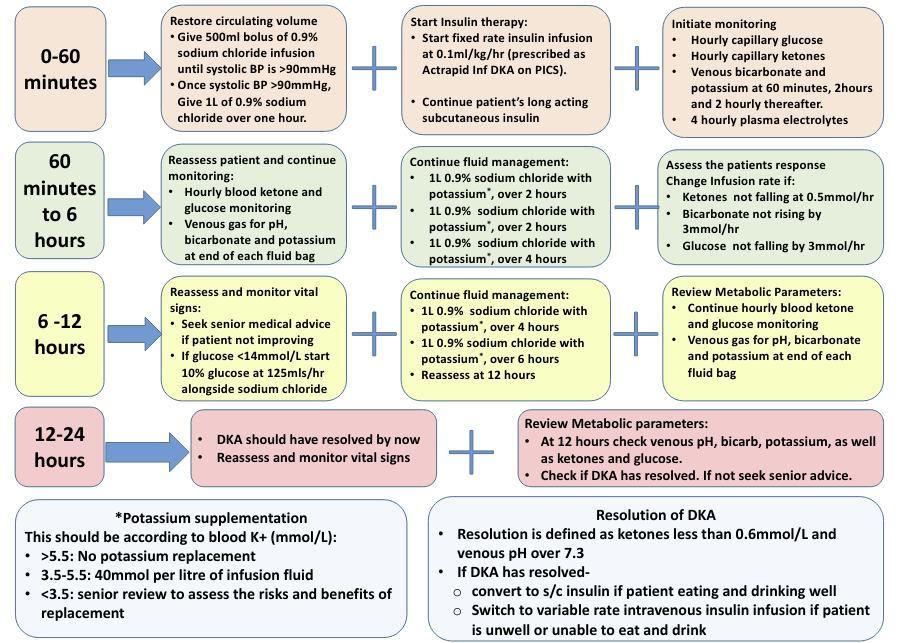

They look something like this:

It's not particularly complex - get a whole bunch of IV access and crack on with the fluids and insulin.

- Keep the blood glucose above 14 mmol/litre

- Don't forget to treat the underlying cause (infection, dehydration, insulin deficiency)

If you do nothing else

Give fluid.

As a wise and slightly scary ED consultant once told me:

"The solution to pollution is dilution"

The dehydration is the patient's biggest problem right now, and adequate fluid resuscitation will not only sort this out, but it will also hugely dilute down the sugar and the ketones and the H+ ions and at least give the kidneys a fighting chance, especially in those patients presenting with a pH below 6.9.

This is why you don't start insulin therapy for a while anyway - the blood sugar will drop fairly signficantly just through rehydration alone, and you don't want to overcook the insulin and send them into hypoglycaemia.

Which fluid to use?

- 0.9% NaCl, Plasmalyte and Hartmann's are all fine

- 0.9% NaCl is probably less good, because of the hyperchloraemic metabolic acidosis that it causes, however the reason most DKA protocols still use it is because of the potassium

- You can't safely add supplementary potassium to the balanced crystalloids on the wards, and it's far more important to get the potassium replacement right than it is to give a more balanced fluid

So for the first litre or two, any one of the three is absolutely fine, but once you start needing to replace potassium, stick to the pre-made bottles of 0.9% NaCl with your allocated mmol of K+.

Unless you're on ICU and giving K+ centrally, then do what you usually do, which is whatever the consultant who is currently on call likes to do for their DKA patients.

How to give a fixed rate insulin infusion

- 50 units of soluble human insulin - usually actrapid

- 50ml 0.9% NaCl*

- Put in a pump and give at 0.1 units/kg/hour

*Quick maffs will tell you this results in a 1 unit per ml solution, which makes pump logistics easier.

If you've done this and you're not making progress, you may need to increase the infusion rate, but don't go above 15 units per hour without talking to someone a tad more experienced.

What you're aiming for

- Ketones to come down by at least 0.5 mmol/litre per hour

- Bicarbonate to increase by 3 mmol/litre per hour

- Blood glucose to reduce by 3 mmol/litre per hour

Keep the fixed rate infusion going until the ketosis has gone, and make sure the patient has had some long acting subcut insulin to prevent it coming back again.

What to do if the blood glucose drops below 14 mmol/litre

- Continue the FRIII

- Double check the glucose (CBG and blood gas) to ensure correct reading

- Start 10% glucose at 125ml/hour

Higher concentrations can be given at appropriate rates in theatre if big/central enough access available.

Just remember to factor this fluid into your resuscitation calculations!

When should I get ICU involved?

Much of the time, DKA patients go from very very sick, to very much better after a few litres of fluid and a bit of insulin, but it's a good idea to give ICU a heads up if a patient comes in with any of the following:

- GCS <12

- BP <90mmHg systolic or significant tachycardia

- Bicarbonate <5 mmol/litre

- Ketones >6 mmol/litre

- pH <7 or anion gap >16

- Hypokalaemia on admission (<3.5 mmol/litre)

What is the mortality of DKA in the UK?

- 0.67% as an average

- Higher in the presence of sepsis, MI, hypokalaemia and lung injury

- Cerebral oedema is the main cause of mortality in children

Other things to consider

- NG tube - diabetic gastric stasis

- Catheter - AKI monitoring

- VTE prophylaxis - mechanical and medicinal

- Antibiotics - if any evidence of infective cause

How do I anaesthetise them?

Most of the time, patients with severe DKA are medical patients and won't need to go anywhere near an anaesthetic (unless it's so severe they need intubating for airway protection of course).

However occasionally you'll be handed a CEPOD booking form for an acute appendix, laparotomy or ectopic pregnancy and then find the patient is also in DKA.

Now, usually you have time to do a fair whack of resuscitation and treatment of the DKA before they need to go to theatre, but there will be the odd occasion where they need surgery immediately, and you'll just have to do your best.

Anaesthetic considerations in DKA

- AAGBI monitoring + awake arterial line (check K before using sux!)

- RSI even if fasted due to gastric stasis (ideally have NG tube in already)

- Aggressive fluid resuscitation initially, followed by goal-directed fluid management (Give a litre of fluid stat before induction)

- Hyperventilate as required to compensate for acidosis

- Central line insertion and central potassium replacement

- FRIII as per protocol

- Think carefully before giving steroids!

You'll need lots of IV access

You might find yourself needing to give all of the following simultaneously.

- FRIII

- Resuscitation fluid

- FRIII fluid

- Anaesthetic drugs

- Pressor infusions

- Blood product infusions

Useful Tweets and resources

Pitfalls in the Management of Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) -#DKA#SodiumBicarbonate#Insulin#FOAMED#FOAMcc

— PAPA (@yednapsarap) May 3, 2024

Top key points👇

https://t.co/9YeTI26NGO

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!