Bronchoscopy

Take home messages

- The key issue is oxygenating a shared airway in a patient with comorbidities

- Local anaesthesia can save you heaps of trouble

- Use TIVA

A spot of history

Meet Gustav Killian, the father of bronchoscopy.

In 1897 this clever chap took an oesophagoscope (posh word for big metal tube) and shoved it boldly down the trachea of a choking patient in order to retrieve a fragment of inhaled bone.

His assistant wrote:

"On March 30th of this year I had the honour to assist my admired principal, Herrn Prof. Killian in extraction of a piece of bone from the right bronchus. This case is of such peculiarity with respect to its diagnostic and therapeutic importance that a more extensive description seems justified."

Things have got a tad more nuanced since that day, but the principles remain exactly the same - put a tube in the tube in the tube - in order to:

- look at the tube

- wash the tube

- take samples of the tube

- remove stuff from the tube

That's it.

A mix and match

Alongside a shared love of staring at vocal cords, performing tracheostomies and a distaste for doing anything south of T4, anaesthetists and ENT surgeons can both find themselves performing some variant of bronchoscopy during their day jobs.

As the anaesthetic contingent in the room, either you're performing the procedure or you're anaesthetising for it - and we'll discuss a bit about both here.

In short, there are two types of bronchoscope:

- Flexible

- Rigid

Flexible scopes used to be fibre-optic - hence the ubiquity of the word - however most scopes are now single use with cameras at the distal end and no fibre-optic qualities at all.

These are the ones used on intensive care and during complicated intubations in theatre.

Rigid scopes are used for surgical procedures and foreign body removal, particularly in children, and remain the remit of our esteemed surgical colleagues.

DIY on ICU

There are two occasions, generally speaking, upon which an anaesthetist might find themselves holding a flexible or fibreoptic bronchoscope with intent to actually use it:

- Awake (or asleep) tracheal intubation in theatre for an expected difficult airway

- Sick intubated patient on intensive care with low sats and lots of secretions or blood

We've talked about the awake intubation bits here, so we'll focus on the ICU bits today.

Why am I doing this?

Existentialism aside, there are three categories of indication for bronchoscopy on ICU.

Diagnosis

- Confirmation of endotracheal tube placement (or tracheostomy)

- Respiratory condition with intraluminal pathology

- Airway burns

- Airway trauma

- Lung cancer diagnosis and staging

Testing

- Bronchoalveolar lavage for sending samples

- Biopsies of masses

- Endobronchial ultrasound

Treatment

- Foreign body removal

- Secretion clearance and pulmonary toilet

- Awake tracheal intubation

- Airway stenting

- Massive haemoptysis

It is generally a fairly safe procedure, when conducted correctly and in the right cohort of patients, and can be very useful both diagnostically and therapeutically.

What can go wrong?

These patients are already the sickest patients in the hospital, with hypoxia, hypercapnia, metabolic and cardiovascular problems already and that's before you've decided to shove a periscope down their throat.

You need to know what physical and physiological effects the act of bronchoscopising has on a ventilated patient.

- The procedure can fail for whatever reason, as anything we do always can

- Hypoxia leads to increased myocardial work, with increased heart rate and blood pressure

- Hypercapnoea leads to acidosis and all of its ensuing changes in vascular resistance (systemic and pulmonary), myocardial output and intracerebral pressure

- Airway trauma can be direct from a clumsily-handled scope or indirect as a result of increased airway pressures from obstructing the trachea and bronchi

- Wild swings in intrathoracic pressure can have knock-on cardiovascular effects

- You can always trigger bronchospasm

- They can always get local anaesthetic toxicity as well

Don't suction for more than three seconds at a time, to prevent excessive atelectasis and hypoxia.

Factors that dramatically increase the risk of bronchoscopy

- Cardiovascular instability

- Acute myocardial ischaemia

- Coagulopathy

- Hypoxia

- Pneumothorax

- Bronchospasm

Explain how you would perform flexible bronchoscopy on the intensive care unit

Preparation

- Check ID, consent and indications

- Ensure stability of unit appropriate for procedure to go ahead

- Rule out contraindications and correct reversible issues

- AoA monitoring

- Adjust ventilator/alarm settings as required

- Ensure NG feed stopped and NG tube aspirated if relevant

- Position patient and monitors appropriately to improve ergodynamics

- Select bronchoscope size (2mm smaller than tube)

- Ensure correct catheter mount on tube to facilitate bronchoscopy

- Emergency airway equipment

- Drugs (rocuronium and sedation)

Procedure

- Experienced operator and adequate assistance

- Check control and orientation of bronchoscope

- Monitor patient and ventilator throughout

Post-procedure

- Re-establish ventilator settings

- Disposal/cleaning of equipment where relevant

- Documentation

- Chest xray

- Review patient once settled

What is BAL and why do we do it?

- Bronchoalveolar lavage

- 20% of intubated patients will get a VAP

- It's thought that aspiration of around 0.3 ml/kg (approx 25ml) of gastric content is enough to cause pneumonitis

- Most bugs can be detected in upper airway or tracheal secretions, but some prefer to dwell in the distance and need deeper sampling

e.g. Pneumocystis jiroveci, TB, other mycobacteria, fungi

- Bronchoalveolar lavage is the gold standard for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia diagnosis, but PCR is increasingly used nowadays

- So you shove a load of 0.9% saline into the relevant segment of the lung and then suck it out again

- The hope is that whatever bug is causing your problem is then detected in these samples when you send it to the lab

If you use 50-60ml, you'll detect things in the more proximal airway branches. You'll need up to 200ml to ensure the whole segment and alveoli get a good washing.

The recommended amount for the exam is 60-180ml.

What's EBUS?

Endobronchial ultrasound.

This variant of flexible bronchoscopy incorporates an ultrasound probe rather than a camera.

One can take transbronchial needle aspirations of cysts, lumps and bumps

What's ultrathin bronchoscopy?

Have a guess.

It's just really slim, thus allowing for examination into the fourth generation of airway and potentially a bit beyond.

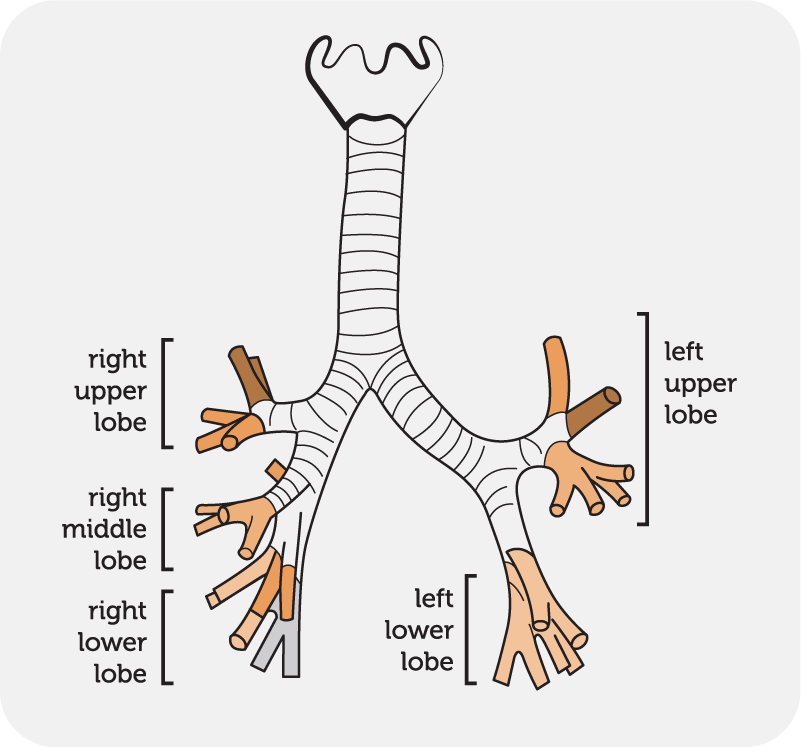

Some anatomy

What the journey looks like

- Trachea ends after 12 cm at the carina at T4/5, branching into right and left main bronchi

- The carina looks slightly off centre because the right main bronchus is a couple of millimetres bigger than the left

- The trachealis muscle runs down the back of the trachea, and can be used as a visual reference during bronchoscopy

Head down the right

The right main bronchus is 25mm long.

The right upper lobe bronchus shoots off at 12 o'clock, and branches off to give three segments

- apical

- posterior

- anterior

The 30 mm right bronchus intermedius then continues before firing off the middle lobe bronchus, which has two branches:

- lateral

- medial

Finally we end up at the lower lobe bronchus, with five segments:

- apical

- posterior basal

- anterior basal

- lateral basal

- medial basal

Head down the left

The left main bronchus is 50mm long.

The left upper lobe has a superior division and lingular division.

The superior division has three segments

- apical

- posterior

- anterior

The lingular division also has two

- superior

- inferior

Finally the lower lobe has four segments

- apical

- lateral basal

- anterior basal

- posterior basal

Bronchi become bronchioles which become terminal bronchioles and then respiratory bronchioles and then alveoli.

How to keep them asleep

If you're scoping a patient on intensive care then chances are they're already intubated and sedated, in which case - crack on - and use a spot of muscle relaxant to stop them coughing when you bump into the carina.

If you or the surgeon are doing flexible bronchoscopy as an elective or semi-elective procedure on an awake patient then they don't necessarily need a general anaesthetic - you can do lots of local anaesthesia +/- some sedation.

Factors affecting your choice of anaesthetic

- What the surgeon wants to do - flexible vs rigid

- How long it's likely to take

- What they want to achieve - quick look vs lots of biopsies

- Patient condition - physiological and psychological

For rigid scoping however you're going to need them asleep, as this is far more stimulating, and much worse news if the patient starts flailing around mid-procedure.

Your options are comfortingly familiar:

As per the norm, you will choose based on your own experience, confidence and most importantly - what your boss normally does.

What are the advantages of inhalational anaesthesia and TIVA for bronchoscopy?

TIVA

- No worries about being able to maintain anaesthesia

- No accidental anaesthesia for everyone else in the room

- Can use for MH patients or if volatiles not appropriate for other reasons

Volatile

- Bronchodilatory effect

- Automatic depth of anaesthesia monitoring

- Can keep the patient spontaneously breathing more easily

How to ventilate them

Again, if they're intubated on ICU and there aren't any surgeons around, then this is largely dealt with already - you just have to make sure you're keeping the patient oxygenated enough and the CO2 isn't climbing too high.

This might require the occasional break to ventilate the patient's CO2 back down to a more manageable level.

If you're in theatre for rigid bronchoscopy, then things are a smidge more complicated.

You've got a shared airway with the surgeon, so trying to manage their airway feels a bit like this.

Your three main concerns are:

- Oxygenating the patient

- Maintaining adequate anaesthesia

- Ensuring adequate ventilation to avoid severe hypercapnoea

If you use TIVA then point 2 is sorted.

We kind of accept that point 3 is going to be suboptimal, for a couple of reasons.

- You can't accurately measure ETCO2 as you have an unsealed breathing system

- You can't accurately deliver measured tidal volumes as you're jet ventilating, keeping them spontaneously breathing or whatever method you've resorted to

So let's focus on oxygenation.

You have three options.

Positive pressure ventilation

You can only really do this with jet ventilation, usually via the side port of a ventilating bronchoscope.

- High pressure (400kPa) jet of pure oxygen uses venturi effect to entrain room air at very high flow

- Can do high or low frequency jet ventilation

- Can be via supraglottic, subglottic or transtracheal

- Generally generates enough tidal volume with passive expiration*

- Can cause barotrauma so needs careful monitoring

*These are still small tidal volumes of up to 3ml/kg mind.

Apnoeic oxygenation

You strap high flow nasal oxygen to their face and hope that some of it ends up in the alveoli

- Also seems to slow the rate of CO2 rise

- Needs very careful patient selection

- Only acceptable for short procedures

Spontaneous ventilation

- Sounds pretty ideal, as you would for a foreign body in a child

- Keep them breathing and avoid the trouble of ventilating them altogether

- Can do it with TIVA as well

Tough to get right because you often end up needing to give opioids and paralytics for the surgeon.

Many patients don't have the physiological reserve or body habitus to facilitate adequate spontaneous respiration under anaesthesia without obstructing their airway or desaturating rapidly.

Airway stenting

We've done a full post on airway stenting here

But we'll quickly recap on the main points.

Categorising lower airway obstruction

Any tube can be obstructed by an extraluminal or intraluminal cause.

- Extraluminal - mediastinal tumour, thyroid goitre

- Intraluminal - bronchial carcinoma

Indications for a stent

Break this down into malignant and non-malignant.

Stenting for malignant causes is usually palliative.

- Malignant - primary cancer, metastasis

- Non-malignant - anastomotic strictures, tracheal stenosis, tracheobronchomalacia

Stents are avoided where possible in benign disease as they don't definitively fix the underlying problem and tend to move around and cause problems after a few years.

If you have to intubate them, then do it with a fibrescope to ensure you don't prod the stent and make your day more stressful than it already is.

Post op

Lie them bad side down, so that any bleeding doesn't dribble across into the good lung and make everyone's day a whole lot worse.

Monitor for signs of what can only be described as the 'reverse coroner's clot' causing airway obstruction.

Pain relief as required.

If any concerns - may need another look.

That's it really.

Here's our post on inhaled foreign body

Useful Tweets and Resources

If you fail direct laryngoscopy in an infant <5kg what is your plan?

— 𝘈𝘯𝘢𝘦𝘴𝘵𝘩𝘦𝘴𝘪𝘢 (@Anaes_Journal) April 2, 2025

In this study, first attempt success was 43% with videolaryngoscopy and 62% with flexible bronchoscopy.

Would you use a bronch in a baby?#anaesthesia #PedsAnes #medicinehttps://t.co/AH2LUABsbb pic.twitter.com/g1rIzEGdT8

(2/3) Check Bronchoscopy revealed B/L endobronchial growth in Left and Right Main Bronchus. Rigid Bronchoscopy performed under General Anaesthesia. Electrocautery snare and Cryobiopsy tool used for debulking. pic.twitter.com/8LWJ8XZ47f

— Dr Sameer Arbat 🫁 (@arbat_dr) July 8, 2020

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.