BRASH Syndrome

Not a lot of people have heard of BRASH syndrome, as it's really only been recognised as it's own thing in the last three or four years, so we decided to do a little post on it here, with the key bits you need to know.

Sound familiar?

An elderly patient presents seriously but non-specifically unwell to ED. They're on a standard cocktail of meds including a statin, beta blocker, ACEi and maybe something bleedy for their atrial fibrillation.

They report being a bit 'off' for a few days, maybe not drunk enough and now they're headed for multiple organ failure with AKI, hypotension, bradycardia, high potassium (but not really enough to cause all this badness) and general everything-shutdown.

Classic BRASH syndrome.

BRASH syndrome

- Bradycardia

- Renal failure

- AV node blocking medication*

- Shock

- Hyperkalaemia

*Usually a beta-blocker, diltiazem or verapamil

Here's what happens

- You start with some injury or insult that causes renal injury

- This causes hyperkalaemia and also build up of the AV blocking drug

- Together these work synergystically to cause bradycardia and reduced cardiac output

- This leads to shock

- This worsens the renal failure

Oh look a spiral of terribleness.

So who gets it?

Well unsurprisingly it's people on AV node blocking drugs who get an unexpected bout of AKI.

Examples include

- older patients

- with infections

- on diuretics

- in the summer

- who've been vomiting

- or had a recent dose change in their ACE inhibitor

Why didn't we know about it before?

Well we sort of assumed something else was going on and treated that instead.

Sometimes the patient got better by accident, and other times we missed it.

Usually there's fairly good-going hyperkalaemia, which we know how to recognise and for which we have a defined treatment pathway, so there's often a knee-jerk response as soon as the first gas comes back.

So most cases of BRASH end up getting diagnosed as hyperkalaemic AKI and left at that.

This isn't the worst thing in the world, as most of the treatment for BRASH is usually covered by treating hyperkalaemia properly, but it's important not to forget the fact that there's some nodal naughtiness going on in the shadows.

How do I know it's not just hyperkalaemia?

- There's a ridiculous bradycardia which isn't going to be adequately explained by just a bit too much potassium hanging around

- The hyperkalaemia is typically fairly mild - the synergism with the AV blocking meds means you don't need a whole lot of excess K+ to slow that node way down

How do I know it's not just AV blocker overdose?

- You won't have a solid history of significant overdose, or at least not enough to explain such a profound bradycardia

- There will be substantial hyperkalaemia which isn't always there when someone overdoses on nodal blocking medications

So how do I fix it?

- Fluid resuscitation (unless overloaded, such as cardiorenal syndrome)

- IV calcium (to stabilise the membrane)

- Insulin and dextrose (to shift the potassium)

- Salbutamol nebulisers (helps with the potassium and the bradycardia)

- Furosemide 80-160mg (to offload potassium)

- Renal replacement therapy (if not responding to furosemide)

- Fludrocortisone can help offload potassium (especially if on anything inhibiting aldosterone like ACE/ARB/spironolactone)

Which fluid?

- If acidotic and hyperkalaemic - isotonic (1.35%) sodium bicarbonate*

- Once bicarb is normal and acidosis improving - Hartmann's or Plasmalyte is fine

*Take a litre of 5% dextrose, take 160mls out and replace with 160mls 8.4% sodium bicarbonate (13.44g) and hey presto - 1.35% solution

Probably best to check with your local friendly intensivist first, and definitely use within 12 hours.

Pressors and inotropes

Even if the blood pressure is normal, you might want to consider a catecholamine, because the patient may well still be hypoperfusing the kidneys if they're profoundly bradycardic.

- Low dose adrenaline if really sick (10mcg every minute or so will help the heart rate, blood pressure and also shove potassium intracellularly)

- Isoprenaline is also an option

Remember calcium!

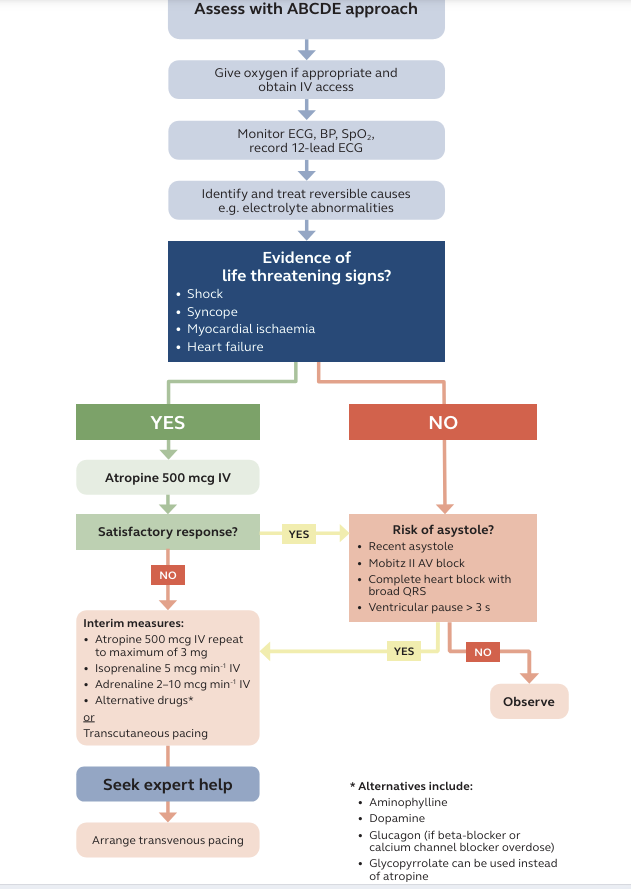

This is probably the key take home message here - look at the resus council guidelines for bradycardia with a pulse.

A patient with BRASH syndrome is likely to be seriously bradycardic but still vaguely pulsatile, and you may well find yourself meandering down this flow chart and never actually manage the hyperkalaemia that's causing the whole problem in the first place.

Some solid tweets

Here’s the #ECG of a patient who presented to the ER with BRASH syndrome:

— Sam Ghali, M.D. (@EM_RESUS) November 25, 2019

B-radycardia

R-enal Failure

A-V Nodal Blocker

S-hock

H-yperkalemia

Note how the bradycardia is out of proportion to the other classic changes of ↑K+ #FOAMed pic.twitter.com/tHq4nugMvu

fresh IBCC chapter on BRASH syndrome!

— 𝙟𝙤𝙨𝙝 𝙛𝙖𝙧𝙠𝙖𝙨 (he/him) 💊 (@PulmCrit) September 28, 2020

😝 synergy between hyperkalemia & AV nodal blocker ➡️ vicious spiral

😝 treatment = simultaneous management of bradycardia & hyperK 💣

😝 organized approach usually avoids need for invasive tx (dialysis or pacing)https://t.co/joHdstYpym pic.twitter.com/UKltK2Qy4w

Just saw my first (recognized) case of BRASH syndrome. Patient presented with bradycardia, AKI, mild hyperkalemia and shock, whom used BB and had dose modified weeks prior.

— Victor Costa (@jvgcostaa) February 20, 2021

Shoutout to @EM_RESUS and @PulmCrit for presenting this!

Q: is it necessary to have hiperK changes in EKG? pic.twitter.com/POXfjKhGXP

Further reading and references