Analgesia for Thoracotomy

Take home messages

- Thoracotomy is probably the most painful procedure to undergo

- Regional anaesthesia is a must, as part of a multimodal analgesic strategy

- These patients are at high risk of chronic post operative pain

The quickest way to a man's heart

Is usually via some sort of thoracotomy.

I know it will come as a complete surprise to you dear reader, but having one's chest cracked open like a well-taped Amazon box is remarkably uncomfortable.

Some History

On the fifteenth day of September 1902, upon a kitchen table in Alabama (Montgomery if you're interested), lay a thirteen year old boy by the name of Henry.

Said boy was busying himself with the process of dying, courtesy of a stab wound to the left ventricle inflicted by another young scoundrel, and as a result one Dr Luther Leonidas Hill decided this would be a simply splendid time to do the world's first documented (and also successful) emergency thoracotomy.

Move over 'see one, do one, teach one' - this dude hadn't seen an abdominal operation until he performed one for the first time.

Alone.

On himself.

He'd also never actually operated on a living heart prior to slicing this unfortunate child open, which rather puts my "I should probably watch another spinal before I have a go" to absolute shame.

Two catgut sutures to the ventricle later and the boy was alive, and presumably in rather a lot of pain, not that Dr Hill would mind all that much, what with his immediate promotion to Legend status.

(Look at his face again and imagine calling him on a Sunday night because scans are 'consultant only' after five - shudder).

Enter Anaesthesia

Apart from adjusting table heights and finding reasons to justify an even bigger cannula, one of our jobs as the anaesthetist is to do our utmost to alleviate the postoperative pain induced by such an invasive procedure.

Not only is pain best avoided for Hippocratic and revalidation purposes, it leads to a number of avoidable complications after the operation.

Furthermore if not well controlled, up to half of patients will go on to develop chronic pain as a result.

You get pain after a thoracotomy for several reasons

- Nociceptive pain from all the slicing and dicing*

- Neuropathic pain from both somatic and visceral afferent fibres

- Referred pain**

- Inflammatory mediator release and primary sensitisation***

*Don't say slicing and dicing in the exam, say medical things like skin incision, rib retraction, muscle dissection, damage to the parietal pleura and chest drain insertion.

**Referred pain tends to be via the phrenic nerve to the ipsilateral shoulder, and can be reduced to some extent through local anaesthetic infiltration of the phrenic nerve at the pericardial fat pad, or with an interscalene block. (Trying to get C3,4,5 coverage with a thoracic epidural is rather sporting)

***Primary sensitisation is where inflammatory mediators such as histamine and bradykinin not only activate nociceptors, but also reduce the pain threshold, making the patient's perception of the pain even worse.

The issue with poor postoperative pain control is that all the time the patient is in pain, they're getting hyperstimulation of the dorsal horn neurons and in turn the higher pain centres via NMDA receptors as a result of three main mediators:

- Substance P

- Glutamate

- Calcitonin

This gradually produces a state of central sensitisation, and you can see where we're headed here - increasing difficulty in getting on top of acute pain, as well as predisposition to chronic pain problems.

Pain words you need to know

- Hyperalgesia - exaggerated pain response to painful stimulus

- Hyperpathia - exaggerated response to any stimulus

- Allodynia - pain response to non-painful stimulus

- Dysaesthesia - abnormal, unpleasant response to light touch

There's a weird paradoxical situation where the patient has reduced input from pressure, temperature and light touch receptors, but hypersensitivity of pain receptors, making everything a whole lot more unpleasant.

Nerve supply

This sometimes comes up in the exam, and is a hard one to guess, so it's worth sitting down with a coffee and a picture, and just trying your best to understand it in the way that has got you through every other anatomy question you've survived up until this point.

The highest yield facts to know (in our humble opinion) are as follows:

- Anterior cutaneous branches of the intercostals pass through the anterior thoracic wall next to the sternum

- Then they split into medial and lateral branches, supplying sensation to the anterior wall of the thorax

The intercostals also supply the following muscles:

- Intercostals

- Subcostals

- Serratus posterior

- Transversus thoracis

They also supply:

- Periosteum of the ribs

- Parietal pleura

- Lateral diaphragm

The central diaphragm is supplied by the phrenic nerve (hence the referred pain to the shoulder).

The visceral pleura receives sympathetic and parasympathetic autonomic supply from the pulmonary plexus.

A multimodal approach

As you might expect, the best approach is to attack the pain from as many angles as possible, rather than trying to rely on a single best technique with enormous doses of whatever you've decided to use.

So as always, your options are:

- Regional anaesthesia

- Paracetamol

- Non-steroidals

- Opioids

- Adjuncts

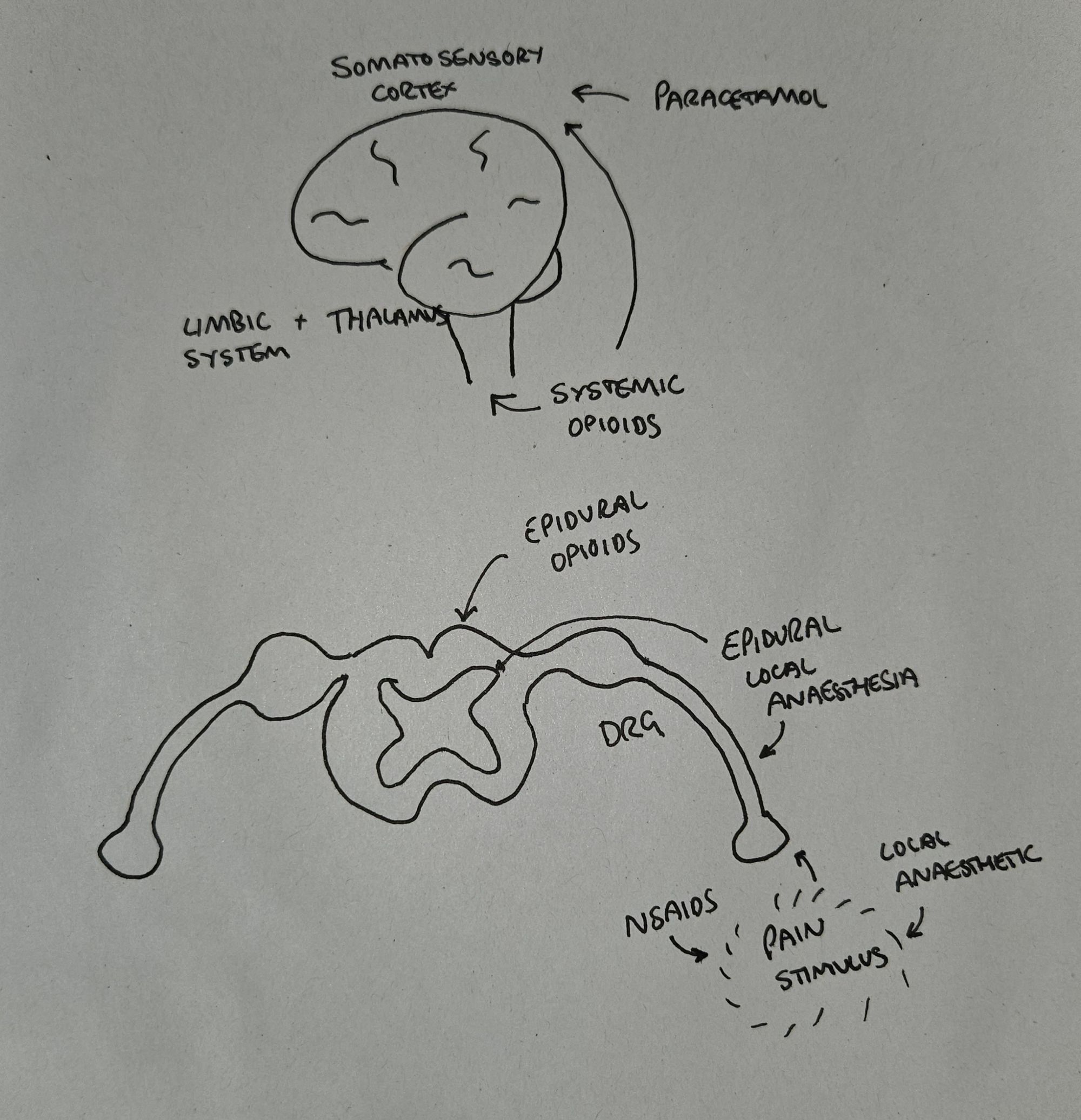

Where do they work?

It's quite nice to know why you're giving a medication and where it's having its effect.

This completely anatomically accurate drawing gives a rough idea of the different sections of the pain pathway we're trying to target, in order to keep the patient as comfortable as possible.

Regional Anaesthesia

As is increasingly the trend in pretty much any operation nowadays, regional anaesthesia has become the mainstay of postoperative pain control for thoracotomies, with two main contenders:

- Thoracic Epidural Analgesia (TEA)

- Paravertebral Blockade (PVB)

Thoracic epidurals and paravertebral blocks both work well to achieve the following:

- Block pain signals from both somatic and visceral afferent fibres

- Reduce neuropathic pain from damage to intercostal nerves

But neither technique is able to deal effectively with referred pain via the phrenic nerve.

Hence the interscalene block is often employed as well.

When you're asked in the exam...

Paravetertebral block is the superior choice for post-operative pain control according to the PROSPECT consensus

Epidurals result in more hypotension, urinary symptoms, itching and nausea and vomiting. There is also the risk of spinal haematoma that occurs with any neuraxial procedure, which a paravertebral approach can avoid.

PVB can be used (with caution) in patients with coagulopathies that contraindicate neuraxial procedures, as this is a relative contraindication to PVB rather than absolute.

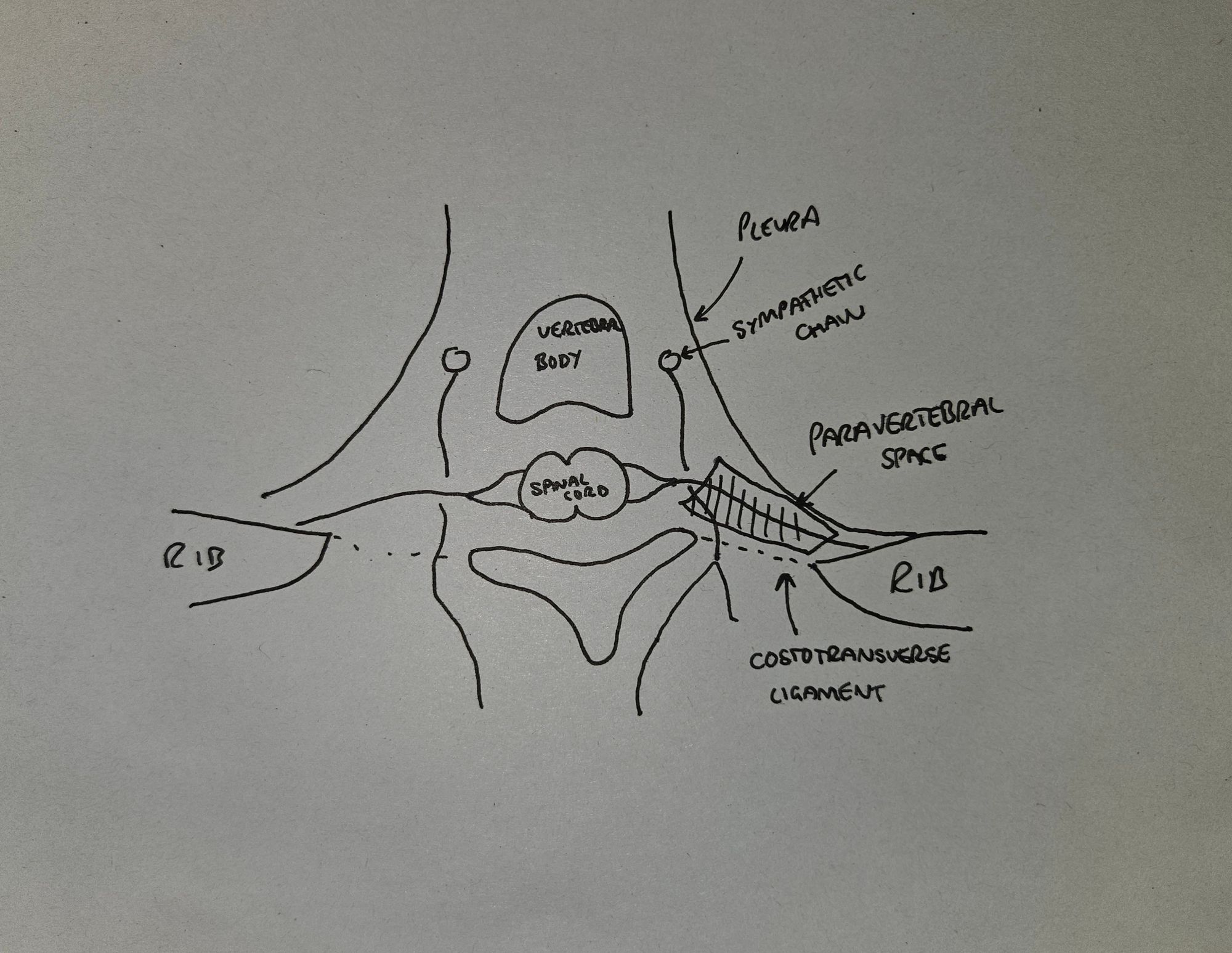

Describe the anatomy of the paravertebral space

- This is a potential space that runs laterally to the vertebral column

- It is posterior to the pleural space

- It is anterior to the costotransverse ligament

- It contains the anterior and posterior rami of the spinal nerves

- It also contains the white and grey rami communicantes

If you're doing an open thoracotomy then the surgeon can usually reach the paravertebral space fairly easily, meaning a surgically placed catheter can be the best option.

The evidence suggests it doesn't really matter whether the surgeon or the anaesthetist sites a paravertebral catheter, so probably best to do whatever works in your hospital.

Just note that if the surgeon is messing around with the pleura or paravertebral space (eg extensive pleurodesis) then the spread of local anaesthetic from a PVB becomes less reliable.

Other options

You can use other regional techniques, such as:

- Erector spinae plane block

- Serratus anterior plane block

- Intercostal nerve blocks

However they haven't demonstrated superiority (or even equivalence) to TEA or PVB so they usually don't get used, unless the other two are contraindicated.

Issues with intercostal nerve blocks

- Higher risk of local anaesthetic systemic toxicity

- No coverage of dorsal rami of the spinal nerves, making them less useful for a posterolateral approach

- They're less effective than paravertebral catheters in VATS

In general a PVB or TEA is preferred, but of course if both of these are contraindicated, then an intercostal block is better than nothing.

Should I block before or after surgery?

It makes logical sense that putting a regional block in before you start slicing is a good idea. It seems that it doesn't make a huge amount of difference for post operative pain whether you do it before or after the first incision, but it is likely to reduce intraoperative opioid use if the patient is already nicely numbed up.

It may also reduce the central sensitisation process, but again - not enough evidence yet to say with any certainty.

Clearly a surgically placed paravertebral catheter is rather tricky to accomplish before an incision - so it will depend on how your surgeon and department like to do things.

Pleural catheters

In 1984 someone was clearly bored with putting their catheter in the convential places and thought to try sticking it between the pleura.

It's not an unreasonable assumption to make - that a swill of local anaesthetic in an anatomically logical location is going to help the patient - however this technique has steadily fallen out of fashion as it has been demonstrated to be inferior to the other options available.

Probably because the pleural space gets all full of air, blood and fluid during the surgery, making the spread of local anaesthetic unpredictable. Oh and a whole, bunch of it gets absorbed into the systemic circulation.

ESBP and SAPB

The more modern fascial plane blocks such as the serratus anterior and erector spinae plane blocks may be safer than a neuraxial or paravertebral approach, but they haven't yet been demonstrated to be as effective.

Watch this space - the ESPB is after all - awesome

Intrathecal morphine

It used to be recommended, if unable to do a PVB or TEA, that intrathecal morphine infusions be used, however this is no longer the case. It doesn't really work beyond 24 hours post op, and has a whole host of side effects as you might expect.

As always, systemic opioids are best reduced or avoided where possible, but are a very useful back up plan if all else fails.

Chronic pain issues

It will come as no surprise that undergoing one of the most painful operations on the menu frequently results in chronic pain problems.

Characteristically, the pain seems to be a burning or sharpness along the site of the scar, and this can be intermittent or constant.

It can also demonstrate allodynia (pain felt after non-painful stimulus like light touch) and hyperalgesia (much higher pain sensation than expected after painful stimulus).

Performing a less invasive VATS seems to reduce acute pain but doesn't reduce the incidence of chronic pain.

Equally it makes logical sense that if you get on top of a patient's pain in the immediate postoperative period then they're less likely to develop chronic pain, but weirdly there isn't a whole load of evidence to back this up at the moment.

Likewise, pre-emptive pain relief to try and prevent it in the first place also sounds like a good plan, however there's no robust evidence at the moment to say that this reduces the incidence of chronic pain issues.

Maybe there's something else afoot.

Genetics

Everyone has their own pain thresholds and sensitivities, and as with everything in life, it's likely a mixture of nature and nurture - genetics, epigenetics and lived experience will all contribute to how a patient perceives pain after going under the knife.

SCN9A, for example, is a gene for a sodium channel which can mutate in two directions, giving either a loss or a gain of function, producing the following conditions respectively

- Inability to feel pain

- Erythermalgia (spontaneous burning and tingling)

The reason this is relevant to the exam is that there are other potential genetic foci that may be identifiable to highlight patients at risk of hyperalgesia and chronic pain, and may also provide clues as to how to prevent and treat it.

But until then, the answer is paravertebral block.

Useful Tweets and Resources

As always, the team at @regionalanesthesiology never miss - with another brilliant breakdown on this highly useful regional block. We highly recommend you subscribe to their channel, and watch everything they've ever made. (gratefully shared with permission)

Regional analgesia for acute pain relief after open thoracotomy and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

— Critical Care Reviews (@CritCareReviews) July 8, 2023

CCR Journal Watchhttps://t.co/Sp06oA6IDG

Get the latest critical care literature every weekend via the CCR Newsletter - subscribe at https://t.co/nitMzacLrj pic.twitter.com/apBFJaS3pH

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.