Airway Assessment

Take home messages

- Putting the tube between the cords is 10% of the work

- Assessment, identification of a difficult airway, positioning, anticipating and preparing for difficulty is the other 90%

- The vast majority of the time, facemask ventilation with good technique and adjuncts will work - the key is recognising when to do it, and doing it properly

- If you're even slightly worried about an airway - have a very low threshold for awake fibreoptic intubation

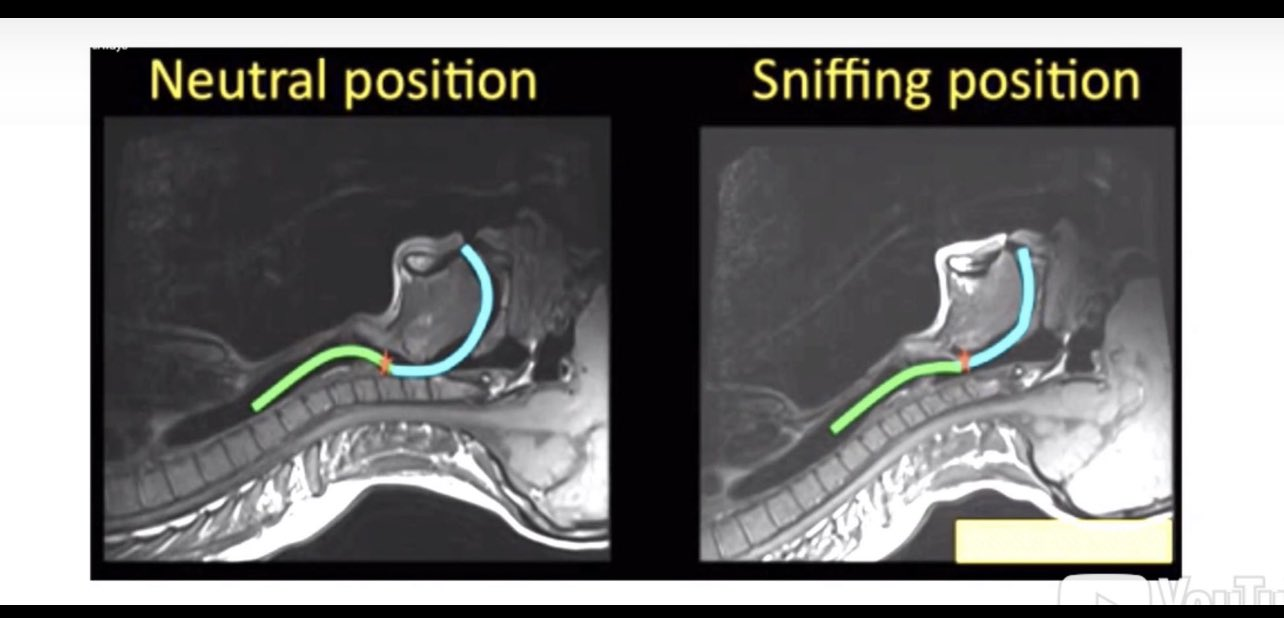

Turning a right angle into a straight line

In essence, the act of laryngoscopy is an attempt to take the right angle between the mouth and the larynx, and straighten it out such that you can see the larynx from outside the mouth.

This then facilitates the insertion of the endotracheal tube between the vocal cords.

While simple in it's essence, the execution is somewhat more complex, and depends on multiple factors:

- Patient

- Pathology

- Practitioner

Fortunately, inability to intubate or oxygenate is rather rare, and we have a host of helpful tips and tricks up our sleeves to help us.

Sometimes it's obviously going to be difficult

Much as one stares rather inappropriately at the veins of fellow train passengers wondering whether one could 'smash in a grey', there are often those passengers that you take one look at and hope that you don't ever have to intubate them.

Especially not on the floor of a train.

Read this whole twitter thread, it's really rather good:

Jabba the Hutt- difficult neck anatomy, low FRC (but good mouth opening) pic.twitter.com/0HtWRZhUiC

— St George's anaesthetic department 🌈 (@StGgas) January 3, 2022

Sometimes it's not so clear

While genuinely difficult intubation is fortunately relatively rare, unfortunately this makes it tricky to develop a test that accurately predicts who is likely to represent a challenge when it comes to airway management.

As a result, many different people have come up with sets of parameters to test, which they feel best predict the likelyhood of a challenging day in the office.

Now it is important to remember that our priority is delivery of oxygen to the patient, and so we can look at each of the different ways of oxygenating in turn:

- Facemask ventilation

- Supraglottic device ventilation

- Intubation

- Cricothyroid or infraglottic ventilation

This might start to look a lot like the DAS algorithm...

Let's look at each in turn.

Facemask Ventilation

The simplest way to keep your patient alive - you hold a mask to their face and puff oxygen in and out through their mouth and nose.

Thus the oxygen has to traverse the oro- or nasopharynx, the back of the tongue, round the corner to the hypopharynx, the larynx and into the trachea.

Plenty of opportunity for problems here.

What is the definition of difficult facemask ventilation?

- Defined by The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA)

- as "the inability of the unassisted anaesthetist to maintain the saturations (SpO2 ) above 90% using a FiO2 of 100 per cent and positive pressure ventilation where the patients’ saturations were above 90% prior to intervention"

- Or "the inability of said anaesthetist to prevent or reverse the signs of inadequate ventilation during positive pressure ventilation."

It can be graded as follows:

- Grade 1 - manageable with a facemask

- Grade 2 - manageable with a mask plus oropharyngeal airway, with or without muscle relaxation

- Grade 3 - difficult despite OPA and relaxation, requiring two operator technique

- Grade 4 - unable to facemask ventilate

Below are some of the risk factors identified that make facemask ventilation more tricky:

Murphy and Walls - MOANS

- Mask seal - beards, blood, broken bones - anything that disrupts a good seal with the facemask

- Obesity - BMI >26 (also pregnant women)

- Age >55

- No teeth

- Snoring or stiff - including bronchospasm and neck irradiation

Langeron's Five

- Age over 55

- BMI over 26

- Beard

- Edentulous

- Snoring

Two or more of these meant there was a high likelihood of difficult facemask ventilation (72% sensitive, 73% specific)

Kheterpal's six

- BMI over 30

- Beard

- Mallampati 3 or 4

- Age over 57

- Poor jaw protrusion

- Snoring

Snoring + thyromental distance <6 = bad news

Sleep apnoea + strange neck anatomy = bad news

Add in neck radiation = seriously bad news

And remember - you can shave a beard and keep their dentures in - but the other things you might just have to put up with.

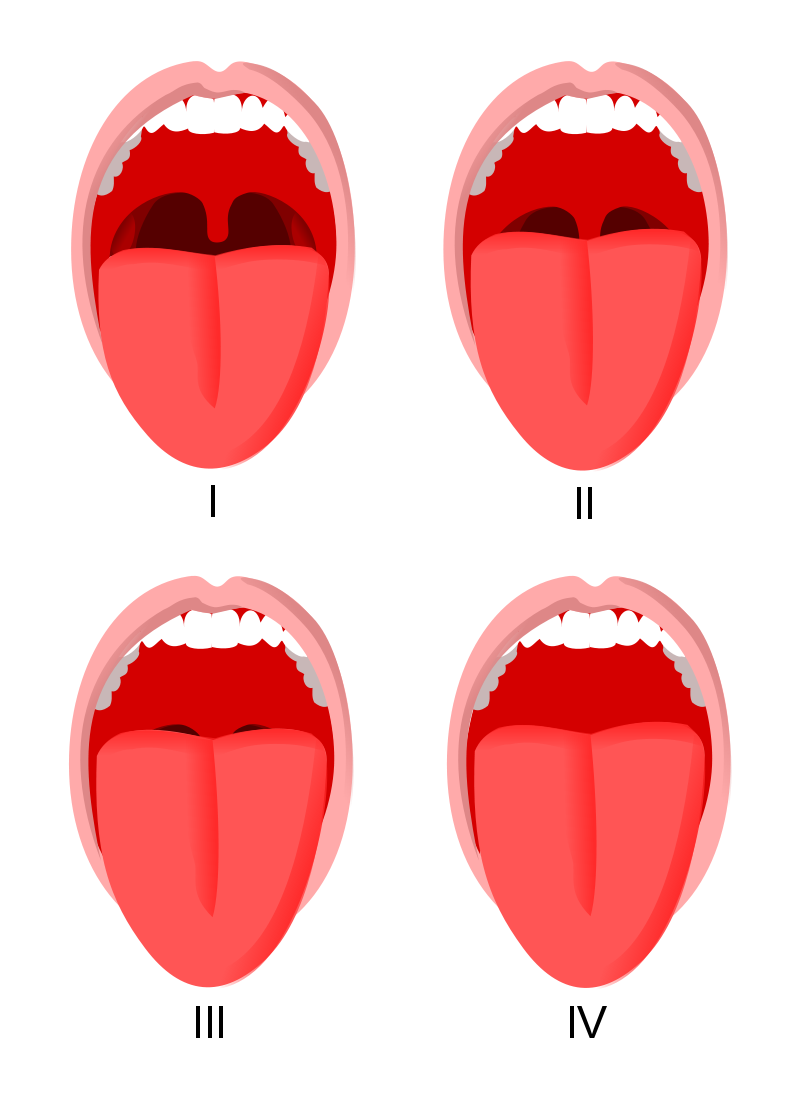

Mallampati score

Now seems like a good time to mention what 'Mallampati' is.

In 1985, Indian anaesthetist Seshagiri Mallampati asked a patient to:

"Open your mouth and stick out your tongue"

What can you see?

- Class I: Soft palate, uvula, fauces, pillars

- Class II: Soft palate, major part of uvula, fauces visible

- Class III: Soft palate, base of uvula visible.

- Class IV: Only hard palate visible

Technically this is the 'modified' mallampati score, because the original score only had three classes.

But this is the one you need to know.

What do the numbers mean?

- Class 1 and 2 have low rates of failure to intubate

- Class 3 has an intubation failure rate of >10%

A bit about mouth opening

Apart from the odd nasal intubation - awake or asleep - the majority of our work is done in the patient's mouth, so it's helpful if they can open it at least a little way to facilitate this.

The numbers that matter

- An inter-incisor distance of less than 5cm (2-3 finger breadths) means direct laryngoscopy is likely to be difficult

- Less than 2.5cm will make a supraglottic airway device tricky to insert

Patients may not be able to open their mouth for two reasons:

- Mechanical problem - TMJ dysfunction, locked jaw

- Pain problem - dental abscess, trauma

Usually if it's a pain problem, then the mouth opening becomes much easier when you've drifted them off to sleep and given them muscle relaxants. However if the problem is mechanical, then you might find yourself in a bit of a pickle.

Hence it's good to try and work out which of these two is the limiting factor before you trundle into your induction.

As always - if in doubt, awake fibreoptic intubation is your friend.

Supraglottic Airway ventilation

It's always reassuring to receive an obtunded patient - from a slightly tachycardic paramedic - with a working IGEL in situ, because you already have your backup plan in place.

If an IGEL is working well before you then try and intubate, then it's likely you can fall back to an IGEL if you're struggling.

But as always in anaesthesia - assume at your peril - prepare for difficulty as you would a fresh native (and potentially soiled) airway.

What's the definition of difficult supraglottic device ventilation?

- The inability to place an LMA (or IGEL) and achieve adequate ventilation - and a patent airway - within three attempts

Adequate ventilation is defined as more than 7ml/kg tidal volume with a leak pressure no higher than 15-20cmH2O.

In their quest to produce a mnemonic for all things airway, Murphy and Walls have devised the following:

Murphy and Walls - RODS

Factors predicting difficult supraglottic airway insertion

- Reduced mouth opening

- Obstruction - especially if this is below the level of the cords

- Distortion - unusual anatomy can prevent a good seal

- Stiff neck or lungs - increased ventilatory pressures can be difficult to achieve with an LMA, and a stiff neck due to radiation can prevent an adequate seal

Difficult intubation

There are many definitions that have been devised for this, and none of them add much more than what it says on the tin - 'tricky to get a tube between the cords'

The definitions you should probably know

- The ASA originally defined difficult intubation as requiring more than three attempts or taking longer than 10 minutes to complete

- 'the clinical situation in which a conventionally trained anesthesiologist experiences difficulty with face mask ventilation of the upper airway, difficulty with tracheal intubation, or both' - Reference

And as you might expect, there are again a variety of different groups that have given their take on which parameters are the most important.

The Australian Critical Incident Monitoring Study (AIMS)

- Limited mouth opening

- Obesity

- Limited neck extension

- Lack of a trained assistant

And as expected, Murphy and Walls are back at it again

The LEMON mnemonic, which you should know for the OSCE

This is for difficult intubation with direct laryngoscopy

- Look

- Evaluate - mouth opening <5cm, Thyromental <6cm

- Mallampati

- Obstruction

- Neck mobility

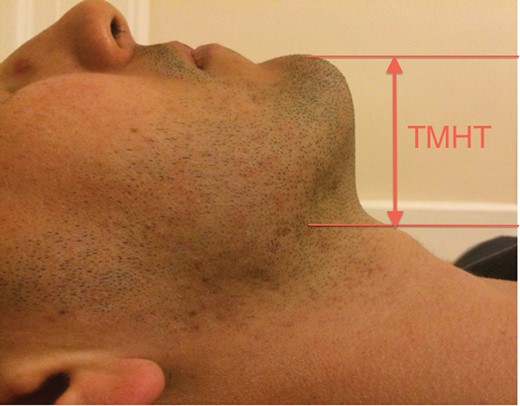

Neck mobility and thyromental distance

As part of our 'sniffing the morning air' intubating position, we want our patient to flex their cervical spine, and extend their atlanto-occiptial joint, to straighten out the airway as much as possible.

'Sniffing the morning air?'

— Phil Poskitt (@PhilDrummer64) April 17, 2018

Think 'Ear to Sternal Notch'. Create the best alignment; optimise the first attempt! #DAC18 #Airways #Intubation pic.twitter.com/pBWu3TbtsL

To get an idea of how well a patient is going to be able to do this, we can measure their sternomental distance.

- Sternomental distance should be at least 12.5cm

We can also get an idea of 'mandibular space' by measuring their thyromental distance. This is the space into which the tongue will be squished by the blade of the laryngoscope, so the more space - the better.

- TMD of more than 6.5cm is reassuring, less than 6cm is likely to be difficult

Once the laryngoscope is in

Technically, laryngoscopy and intubation are two different things, but clearly they're inextricably linked.

This is where Cormack and Lehane come in.

This is the dreaded moment as a novice when your supervisor says:

"What can you see?"

And you'd really really like to be able to say something other than 'pink'.

The 'modified' Cormack and Lehane classification

- Grade 1 - The whole glottis

- Grade 2a - Part of the glottis

- Grade 2b - Only the back of the glottis or the arytenoids

- Grade 3a - Epiglottis can be lifted up

- Grade 3b - Epiglottis can't be lifted up

- Grade 4 - A whole load of nothin

The importance of this scale is that the likelyhood of failed intubation is <1% for Grade 1 but 88% for Grade 3a

So what should I test?

You might be noticing a pattern here.

Even if there isn't a consensus on which ones are the best, the same parameters seem to be cropping up time and again.

Ideally we assess all of the following:

- Any previous problems with airway or anaesthesia

- History of significant oesophageal reflux

- History of sleep apnoea

- Body mass index and presence of obesity

- Mouth opening and inter-incisor distance

- Mallampati score

- Dentition and presence of loose teeth

- Thyromental, sternomental or thyrosternal distance

- Jaw protrusion

- C spine mobility

- History of neck irradiation

60% of the time, it works every time.

The numbers to care about:

The specific numbers that matter

- Mallampati

- BMI and neck circumference - (pay attention if either above 30)

- Mouth opening - >37 mm (Reference)

- Inter incisor distance - 5cm for laryngoscopy, 2.5cm for LMA

- Sternomental distance - >12.5 cm

- Thyromental distance - >6cm

A Caveat about Obesity

In general, the more obese the patient is, the more tricky they are to intubate.

However - it's highly variable, and many patients have high BMI with the weight all distributed in the lower body, and many normal BMI patients have disproportionately thick necks - so don't assume anything.

Just for the exam

If you're asked for a specific answer to predictors of difficult intubation in an exam, the short answer from the RCoA is:

- Mallampati + thyromental distance + good history

The slightly longer answer is

- Meta-analysis of many studies (35 I think) found that Mallampati and thyromental distance were the best tests when combined, but were still only 36% sensitive

- Hence they advise adding in a bit of history to boost the numbers

The most useful thing of all

It's all well and good doing a spectacularly thorough examination of the patient, however in reality there are few things quite as useful as a recent anaesthetic chart with documentation of how hard the patient actually was to intubate.

Even if you've done a dedicated, textbook airway assessment, there are always those occasional surprises, but if you've got an anaesthetic chart saying something along the lines of:

- Uneventful first pass intubation, MAC3, Grade 1 view

- Intubated by novice CT1 (dated 7th August)

Then you can be fairly certain it shouldn't be too tricky.

(But then again, they might have had a neck dissection and radiotherapy since then, so keep your wits about you).

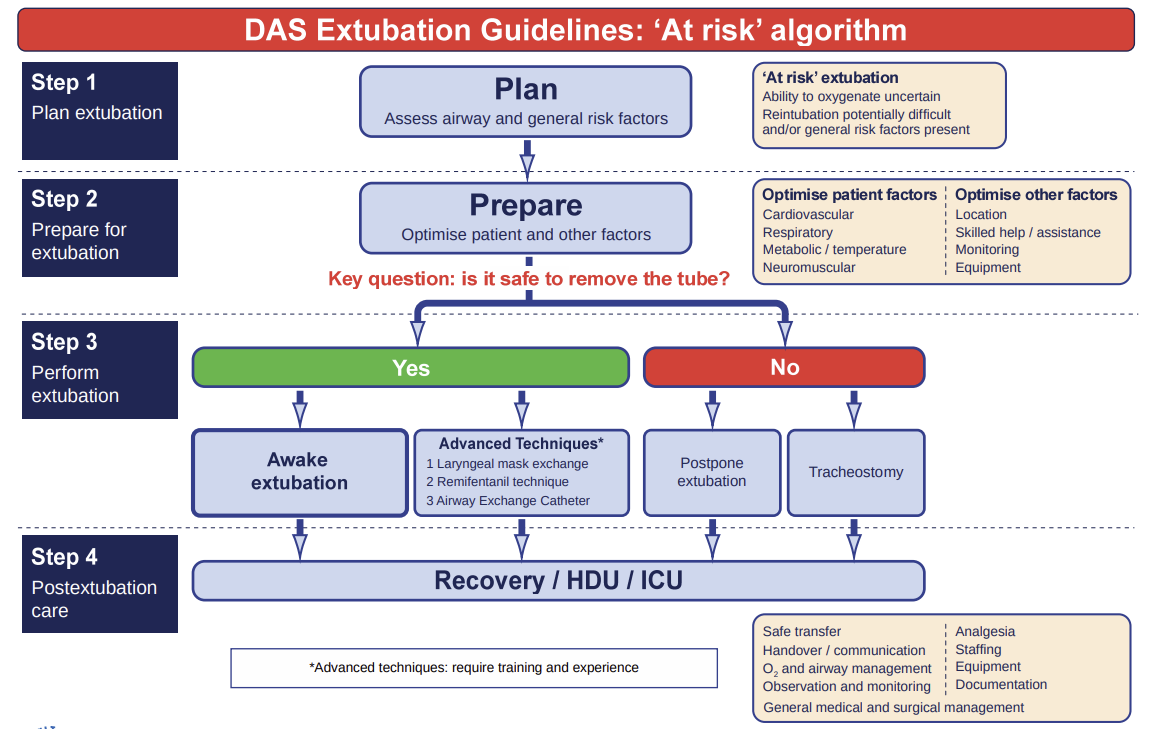

What about extubation?

As always, follow the DAS guidelines and you won't go wrong.

Useful videos

Check out these two videos from gasnovice.com

Free CRQs for the Final FRCA

Head on over to frca-revision.com for well-written, free CRQs and SBAs.

Tap the image below to head straight to their difficult airway CRQ:

Useful Tweets and resources

The science behind the app. Prevent airway complications with a very accurate airway assessment method https://t.co/YtxOREaY2S

— Hans Huitink (@AirwayMxAcademy) December 26, 2022

This is why airway assessment needs to be global. Airway assessment is more than just intubation! Here's a #OnePager showing some mnemonics that can help identify difficult procedures, following the NAP4 structure. #JanuAIRWAY 6/8 pic.twitter.com/ndABGSzIoM

— Difficult Airway Society (DAS) Trainees (@dastrainees) January 2, 2022

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.