Acute Intermittent Porphyria

Take home messages

- Porphyria is complex, and an acute attack can be life threatening

- The definitive management is haem arginate

- Supportive management and adequate analgesia are crucially important too

Podcast Episode

What do you think of when you hear the following?

- Pale skin

- Avoiding sunlight

- Pointy teeth

- Aversion to garlic

- Drinking blood

- Madness or demonic behaviour

So there's this ongoing theory that porphyrias may explain the existence of vampires in folklore.

Porphyria causes anaemia and photosensitivity, as well as psychiatric disturbances. Repeated acute attacks can also lead to periodontal disease and receding gums, giving the teeth a 'fang-like' appearance.

Dark red, blood-coloured urine in those affected by the condition led people to believe that sufferers must have been drinking blood, and apparently some physicians at the time recommended drinking animal blood as a treatment for the anaemia.

The sulphur content in garlic can trigger acute attacks.

Case closed as far as I'm concerned.

The term 'porphyria' comes from the Greek word for purple, denoting the discoloured urine in patients affected by the condition.

So what is it?

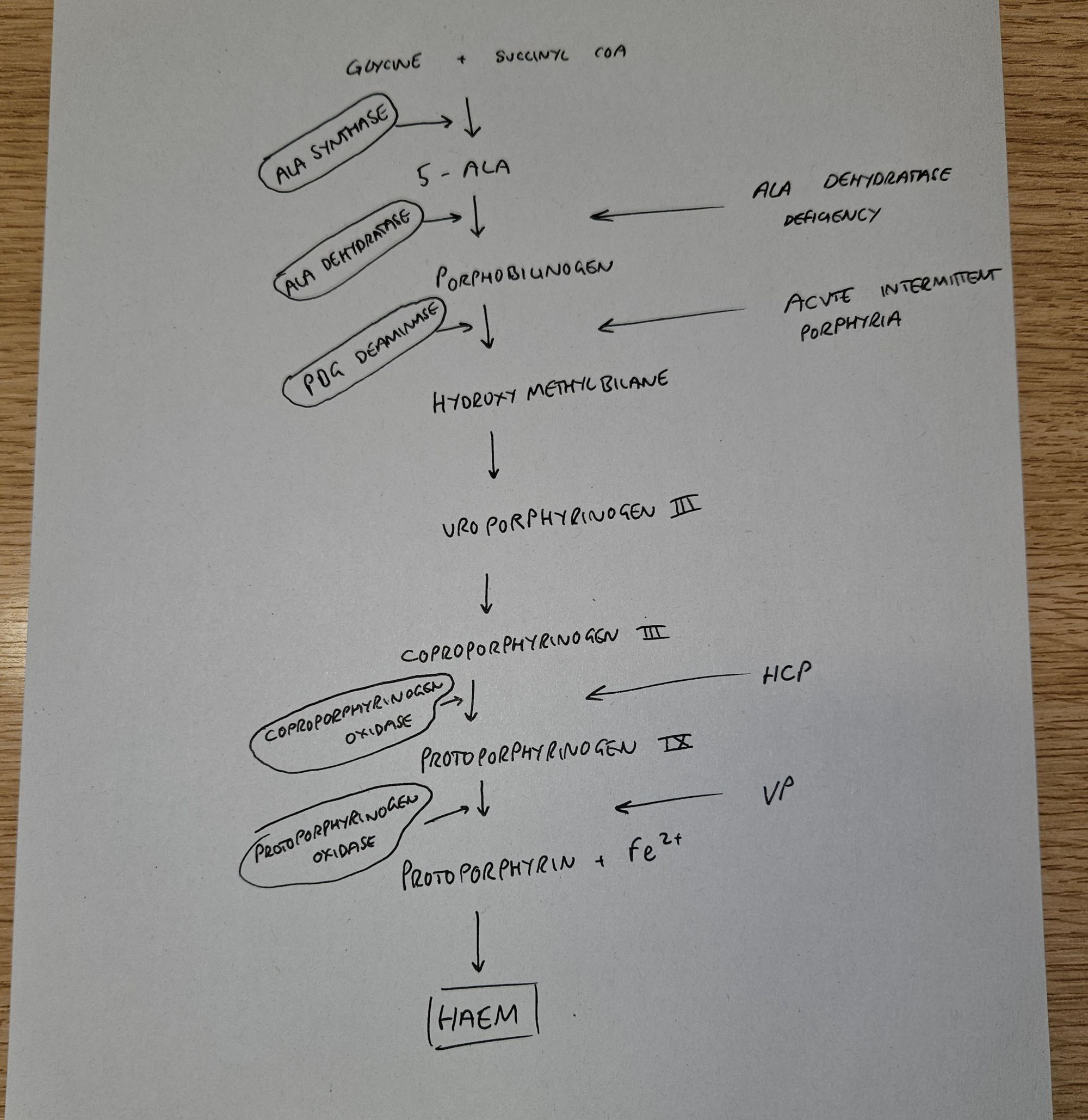

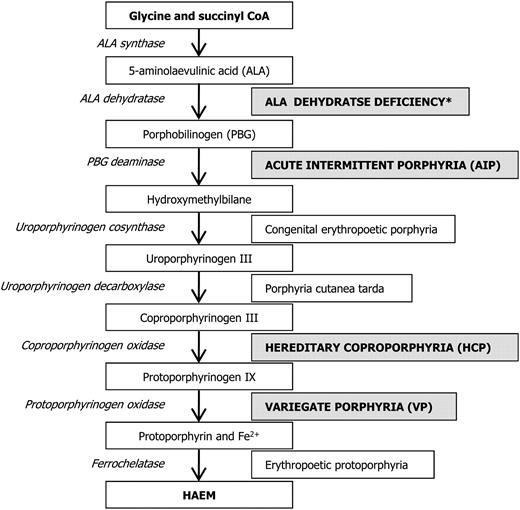

Haemoglobin is rather useful in the grand scheme of things, but it's rather complex to make.

In this multistep pathway, if you have a substantial enzyme deficiency at any point, then you end up with a backlog of precursor molecules, which promptly wander off and start causing havoc in the body.

These precursers are called porphyrins, and the diseases they cause are the porphyrias.

There are lots of types of porphyria, but we most commonly refer to two categories:

- Acute

- Non-acute

As anaesthetists we're generally interested in the acute porphyrias, as these ones present with the neurovisceral crises that can be so tricky to manage well.

There are four types of acute porphyria

- Acute intermittent porphyria

- Variegated porphyria

- Hereditary coproporphyria

- 5-aminolaevulinic acid dehydratase deficiency

Anything that increases the production of haem in the liver, or at least the attempt to produce more haem by the body, is going to cause a build up of these precursors, which then cause the symptoms.

Of the acute porphyrias, acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) is the most common.

So what actually happens?

We don't know.

We think the precursor porphyrins somehow cause nerve dysfunction in peripheral and central nerves, both somatic and autonomic, but we don't exactly know how. It might be that the porphyrins are neurotoxic, it might be a simple lack of functioning haem causing nerve dysfunction.

Very unsatisfactory I know.

For the exam, just say 'neurotoxic metabolites' and move on.

Who gets it?

AIP, HCP and VP are all autosomal dominant, while ALA dehydratase deficiency is recessive.

- More common in females

- Usually between 20 and 40 years old

- Runs in families

It's difficult before an official diagnosis as an acute attack can mimic many other conditions, and previous carrier family members may never have demonstrated any symptoms.

How does it present?

- Classically severe colicky upper abdominal pain

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever

- Motor and sensory neuropathy

- Autonomic dysfunction

- Cranial nerve palsies

- Confusion and low GCS

- Seizures

The Four Ps of porphyria

- Painful abdomen

- Polyneuropathy

- Psychological disturbance

- Port coloured urine

How do I diagnose it?

First you have to think of it, then you need to test PBG or porphobilinogen levels in the urine.

The urine sample can be collected in a normal urine sample container but crucially needs to be protected from light.

This is because the porphobilinogen degrades in light, and risks giving a negative test result.

If the test is positive, you need to start talking to your local specialist centre, who will want another confirmatory sample, as well as a blood sample and faecal sample so they can figure out exactly which type of porphyria it is.

Further down the line, genetic investigation can determine the culprit mutation and family members can be consented for screening as required.

Why does it happen?

Anything that causes a sudden increase in haem production is going to result in these porphyrins being churned out at a rapid rate and potentially cause an acute neurovisceral attack.

What triggers an acute porphyric attack?

- Drugs

- Stress

- Infection

- Alcohol and smoking

- Menstruation

- Pregnancy

- Starvation and dehydration

Fasting

Fasting is a key trigger of porphyrin production so ensure your patient is well topped up with carbohydrate - at least 200g glucose per day.

This can be enteral or parenteral, and IV dextrose has been used to abort more mild attacks via suppression of ALA synthase activity in the liver.

Haem Arginate

Haem arginate clamps down on ALA production by topping up the body's supply of haem, and increasing the negative feedback loop, thereby reducing porphyrin production.

- 3 mg kg−1 (to a maximum of 250 mg)

- Once a day for four days

It is given over half an hour into a large vein or central line as it can cause thrombophlebitis.

Supportive treatment

As with many conditions, a large part of treatment is simply supporting all the correctable bits of their physiology until they get better:

- Airway and ventilatory support if bulbar or respiratory weakness

- Avoid catabolic state with adequate carbohydrate loading

- Betablockers for tachycardia and hypertension

- Electrolyte correction to prevent seizures

- Parenteral opioids for pain relief

- Antiemetics - prochlorperazine and ondansetron

Anaesthetic implications

So let's say you have a patient known to have AIP, booked for an operation on your elective or emergency list.

What are your key anaesthetic priorities?

- Thorough history and exam, particularly with regard to neuropathy, autonomic instability and respiratory function

- What type of porphyria and history of acute crises and triggers

- Avoid stress and anxiety - consider premedication with benzodiazepines

- Minimise fasting time

- IV dextrose

- Not suitable for day surgery

- If considering regional anaesthesia, thorough neurological examination required prior to procedure

You don't need to routinely monitor urinary PBG levels in the absence of clinical symptoms.

How to prevent an attack

- Avoid triggering drugs

- Avoid precipitating features

- Consider premedication to reduce stress

- Minimise fasting time

- Ensure adequate hydration

Useful Tweets and Resources

Here is an updated list of drugs that are safe to use in porphyria, from this site

Quick Take: Treating Acute Intermittent Porphyria pic.twitter.com/w7y2t9tQTT

— NEJM (@NEJM) June 17, 2020

Today I learned:

— Jordan Holloway, MD (she/her) (@jholloway_MD) December 14, 2022

A few anesthetic-related meds not to give to patients with acute intermittent porphyria:

- ketamine

- etomidate

- ketorolac

- barbiturates

- EtOH

- calcium channel blockers

and lots more…#Anesthesia #MedTwitter #MedEd #FOAMed #Anesthesiology #AlwaysLearning pic.twitter.com/Uy5JbxrxRA

References and Further Reading

Primary FRCA Toolkit

While this subject is largely the remit of the Final FRCA examination, up to 20% of the exam can cover Primary material, so don't get caught out!

Members receive 60% discount off the FRCA Primary Toolkit. If you have previously purchased a toolkit at full price, please email anaestheasier@gmail.com for a retrospective discount.

Discount is applied as 6 months free membership - please don't hesitate to email Anaestheasier@gmail.com if you have any questions!

Just a quick reminder that all information posted on Anaestheasier.com is for educational purposes only, and it does not constitute medical or clinical advice.